Shibata Zeshin, 1807-1891

By Natasha Sivanandan

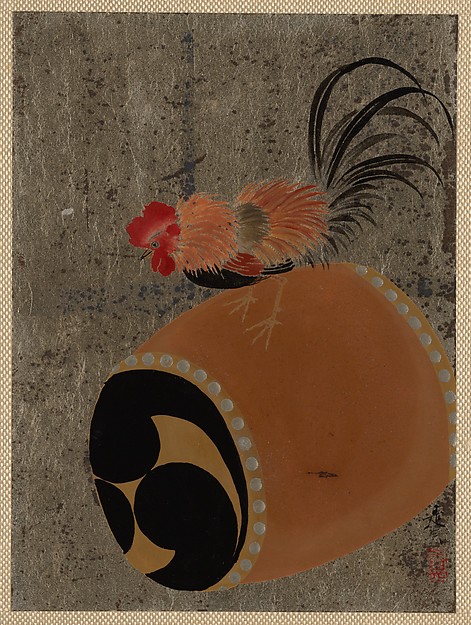

The name Zeshin is a reference to an ancient Chinese fable revolving around a king who wanted to meet the greatest artists in the land. When the artists arrived they all bowed and showed the king proper respect. However, one of the artists arrived late, half-naked and proceeded to sit on the floor and lick his paintbrush. The king would go on to exclaim: “now this is a true artist,”. The word Zeshin has a similar meaning to the Truth, perhaps giving us insight into the creative genius that is Shibata Zeshin. Zeshin would go on to become not only a great artist, but also the creator and innovator of urushi-e; the strange technique of painting with lacquer.

Zeshin was born in the late Edo period and early Meiji era (March 15th, 1807) of Japan, to a family of skilled shrine woodcarvers and carpenters. His father was a qualified ukiyo-e and made woodblock prints and paintings. With the support of his family, at the age of thirteen he apprenticed with the lacquerer Koma Kansai. Kansai was key to Zeshin’s success as he would go on to arrange an opportunity for Zeshin to study with the great painter of the Shijo school, Suzuki Nanrei. Interestingly, during this early artistic period Zeshin had changed his name from Kametaro, to Junzo, to Reisai (a combination of his previous senseis name’s). Finally, he was given the name Zeshin by Nanrei and would keep it for the rest of his life.

After becoming skilled in lacquering, painting and sketching he also encountered and dabbled in Japanese tea ceremonies, haiku and waka poetry—these fields supported the development of the very original technique he would attain as a mature artist. In 1835 he inherited the Koma School workshop and he had a reputation, among his students, for humility. He told them that he wished them not to be known as a pupil of Zeshin’s, but instead as a great artist who had studied and grown under his tutelage.

In the 1830s and 40s, Japan struggled from a serious economic crisis and artists were faced with a strict imposition; to no longer use silver or gold in their art, which was most detrimental to lacquer paintings. Zeshin found a way to use bronze and still produce a metallic texture to his work whilst at once maintaining his decorative and beautiful style. This style was described by many Japanese critics as encapsulating the concept of wabi. Wabi loosely translates to “simple elegance,” something also embodied by the traditions of the tea ceremony and the haiku.

By 1869 Zeshin was commissioned by the Imperial government and sent to several world exhibitions including Vienna (1873), Philadelphia (1874), and Paris (1889). One year before his passing, he received the immense honour of being granted membership into the Imperial Art Committee and remains to this day the only artist to have been recognised as a master in two disciplines; painting and maki-e.

When one gets to experience Japanese lacquer work in galleries, exhibitions or workshops, behind its style and grace is Zeshin, who, to this day, is recognised as the supreme master in this challenging field of art.

Bibliography

Bushell, Raymond, and Andrew J. Pekarik. "Japanese Lacquer, 1600-1900: Selections from the Charles A. Greenfield Collection." Monumenta Nipponica 36, no. 2 (1981): 219.

O'Brian, Mary Louise. The art of Shibata Zeshin. London: R. G. Sawers Pub. , 1979.

Oohasi, Kaiti. "Japanese lacquer and baking japanese lacquer." Journal of the Japan Society of Colour Material 36, no. 1 (1963): 15-19. doi:10.4011/shikizai1937.36.15.

Sandler, Mark H . "Shibata Zeshin [Junzō; Koma; Reisai; Tairyūkyo; Tanzen]." Shibata Zeshin | Oxford Art. November 23, 2017. Accessed March 11, 2018. http://www.oxfordartonline.com/view/10.1093/gao/9781884446054.001.0001/oao-9781884446054-e-7000078233?rskey=NqR8Hi&result=1.

Yonemura, Ann. "Japanese lacquer." 1979. doi:10.5479/sil.124223.39088017645151.