William H. Johnson 1901-1970

By Patrick Heath

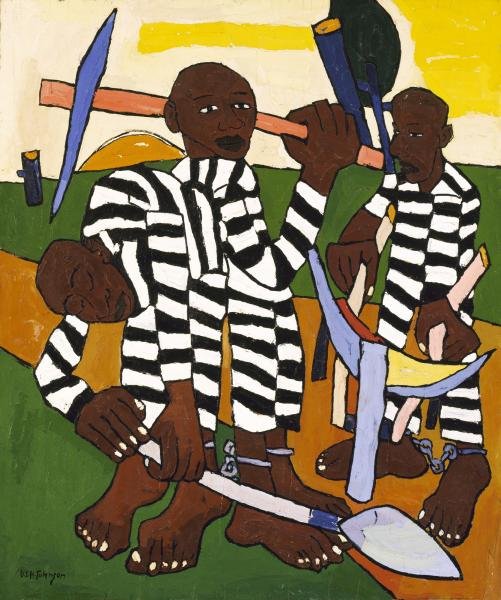

William H. Johnson, Chain Gang, ca. 1939, oil on plywood, Smithsonian American Art Museum

William H. Johnson (March 18, 1901 – April 13, 1970) was an American artist whose work, inspired by the Harlem Renaissance of the early 20th Century, portrays the experience of Black Americans who took part in the Great Migration from the Southern States at the end of the First World War. Johnson’s creative dexterity, whether through the medium of woodcuts, oil, water colour, pen and ink, or serigraphy, produced some of the very best examples of folk art and primitivism in America during the 20th Century. Harnessing influences from across the globe, Johnson managed to adeptly capture the North-South consciousness experienced by African Americans of his generation.

Johnson was born on March 18th, 1901, in a small town called Florence in South Carolina. His parents, Henry Johnson, and Alice Smoot were very poor, and Johnson went to school at the all-black Wilson School in his hometown. Johnson was probably introduced to art at this time by his teacher, Louise Fordham Homes. He used to copy comic strips that he had found in newspapers and even contemplated becoming a cartoonist after he left school. In 1918, aged just 17, Johnson decided to leave Florence for New York city; he moved in with his uncle in Harlem and began working odd jobs to save up money for art school fees. This initial journey was the spark for a remarkably peripatetic life. Johnson enrolled in the prestigious National academy of Design where he was educated in classical portraiture and figure drawing before studying under Charles Webster Hawthorn in 1923. Hawthorn instilled the importance of vibrant colours in the young artist, and he was so impressed by his remarkable capability that he funded a trip to Paris in 1927. In France, Johnson became enamoured with European-style modernism; his early work, which was almost exclusively landscape painting, incorporated the broad brushstrokes and bold colours that he admired in expressionist painters such as Chaïm Soutine. Johnson also met his wife, the Danish textile artist Holcha Krake, in Paris; and, after a brief time spent back in America 1929, he would reunite with her in 1930 and spend the majority of the decade living with her in Scandinavia.

This period, from 1930-1938, would prove to be essential in the development of Johnson’s stylistic values. Being removed from the both the American and Parisian schools allowed him to embrace the folk art popular in his wife’s homeland. The shifting nature of his approach can be seen in the comparison between his landscape paintings in the late 20s and the mid-to-late 30s. His Vieille Maison at Porte (1927) is demonstrative of his interest in the French impressionists, its thick strokes and pure colours create a lovely luminosity in both the highlights and the shadows of the scene. Conversely, in his Harbor, Svolvaer, Lofoten (1937), Johnson foregoes the airy luminosity of his impressionistic work, his brushstrokes get thicker still, and the colours used seem more definite. The resulting painting is full of contrast, capturing the shadowy fishing boats in the harbour and the precipitous mountains that dominate the skyline.

Under the threat of Nazism, Johnson and Krake moved back to New York in the late 1930s. Johnson found work as a teacher at the Harlem Community Art Centre and was immediately immersed once again in his African American heritage. He became committed to painting the experiences of ‘his own people’ and began to adopt a vernacular, self-consciously primitive style that celebrated Afro-American struggle, culture, and tradition; his work was thus characterised by its ‘stunning, eloquent, folk-art simplicity.’ His deeply political and moving subject matter from this later period sits in an uncomfortably dichotomous position with the almost benign nature of his painting. This process is typified in paintings such as Chain Gang (1939) in which he illustrates the realities of incarcerated Black men forcefully engaging in manual labour. In the work, Johnson employs his characteristic pastel blue colour to depict both the tools of the prisoners and the chains that are keeping them bound; the men are adorned with cartoonish black and white striped outfits and the background is constructed of simplistic, yet vivid blocks of blues and greens. The ensuing effect challenges the viewer’s complicity with the playfulness of the composition amidst the backdrop of physical and political violence perpetrated against the Black community in America throughout the artist’s lifetime. Johnson continued to create art of this ilk throughout the 1940s, however following the death of his wife in 1944, his mental health and overall stability suffered a rapid decline. His grieving of her death was compounded by a number of other untreated medical issues that were suddenly brought to the fore, he subsequently experienced a mental breakdown and was institutionalised at a hospital on Long Island up until his death 23 years later. Johnson died on April 13, 1970, of haemorrhaging of the pancreas, and his oeuvre was acquired in 1967 by the Smithsonian Institution’s National Collection of Fine Arts. Johnson’s inactivity in later life contributed to a lasting level of obscurity in the artistic community in the 20th Century; it is only recently that he has begun to be celebrated as one of the most important figures of the Harlem Renaissance.

Bibliography

Michele Simms, ‘Remembering William H. Johnson: A Forgotten Harlem Renaissance Artist’, Abri Art and Culture, https://abriartandculture.wordpress.com/art/remembering-william-h-johnson/ [accessed 14/03/2022]

Jenevive Nykolak, ‘William H. Johnson’, National Gallery of Art, https://www.nga.gov/features/exhibitions/outliers-and-american-vanguard-artist-biographies/william-h-johnson.html, [accessed 14/03/2022]

Leah Dickerman, ‘William H. Johnson’, Museum of Modern Art, https://www.moma.org/artists/22989, [accessed 14/03/2022]

Karen C. Chambers Dalton, ‘Reviewed Work: Homecoming: The Art and Life of William H. Johnson. by Richard J. Powell, Martin Puryear’, The Journal of Southern History

Vol. 60, No. 1 (Feb., 1994), pp. 162-164