Francisco Goya 1746-1828

By Rosie Miller

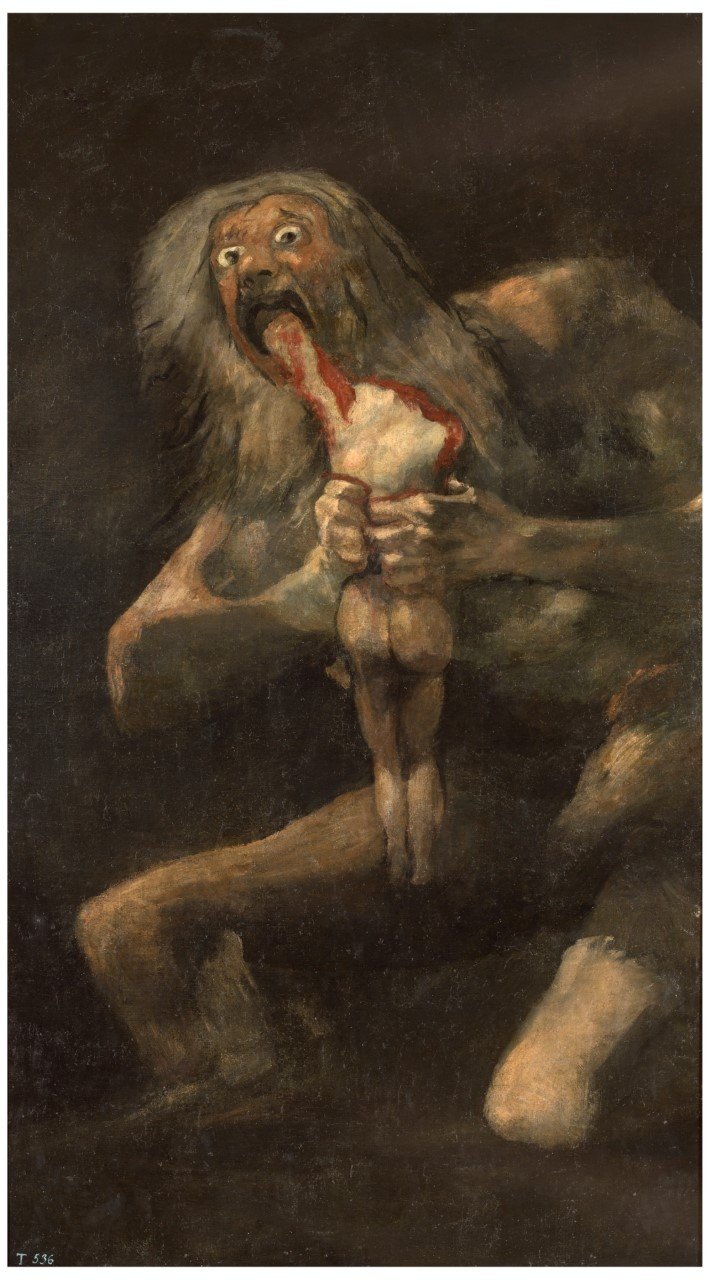

Francisco de Goya y Lucientes, Saturn, 1820 – 1823, mixed method on mural transferred to canvas, 143.5 x 81.4cm, Museo del Prado

A prolific court painter and member of the Madrid Academia, Francisco de Goya is arguably the most highly regarded Spanish artist of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.

Nonetheless, his rise to fame was by no means a foregone conclusion. Given the absence of museums and galleries, young Goya was forced to approach the Academia if he was to make a name for himself, an endeavour which repeatedly proved unsuccessful.

Goya’s artistic association with the Spanish monarchy was therefore humble in origin. From the poorly paid confines of Madrid’s royal tapestry factory, he manufactured a series of cartoons for the royal household.

Despite the modesty of this initial commission, the early stages of Goya’s career aligned with a radical departure in official Spanish art. An enlightened, sympathetic ruler, King Charles III advocated socio-cultural reform; unlike his predecessors, he recognised – and expounded – the value of modern, as opposed to ancient, subjects.

Thus, Goya figure-headed a revolutionary aesthetic programme, in which ‘low brow’ activities were treated as artistically pre-eminent. Many of his subjects were therefore rooted in popular culture, exploring topics as varied as bull fighting, festival culture and southern gypsy communities.

Of equal, if not superior, renown were Goya’s portraits. Stylistically, these were notable for their painterly technique, which emulated in broad brushstrokes the brilliance of royal finery. Goya’s particular skill, however, lay in his profoundly humane treatment of subjects, which were often heavy with personal expression, interior clarity, and a sense of humanity.

Given his commercial success as both a genre and portrait artist, the latter stages of Goya’s career were surprisingly desolate. He received no royal commissions during the tumultuous reign of Ferdinand VII and, having been rendered permanently deaf by a bout of severe illness, embarked on a series of fourteen deeply pessimistic Black Paintings between 1820 and 1823.

Characteristically naturalistic in style, these oil paintings invoke fantastical creatures to sardonic, horrifying effect; in Goya’s hands, Catholicism is reduced to a monkish, humanoid billy goat, while a pagan god, (pictured), feasts on his son’s decapitated corpse. None of these works were dated or even signed by the artist; Goya did not intend them to be seen.

Thus, he could never have supposed that they were to form the prophesying pillars of Expressionism and Surrealism; in the same way that Charles III jettisoned the ancient aesthetic tradition, Modernism afforded Goya a retrospective platform, from which his inner turmoil has been recognised – and exalted – as compelling subject matter.

Bibliography

Rainer Hagen & Rose-Marie Hagen, “Francisco Goya, 1746-1828”, (Taschen, 2003)

Stephen Phelan, ‘Goya's Black Paintings: “Some People can Hardly even Look at Them”’, The Guardian, 30 January 2019, https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2019/jan/30/goya-black-paintings-prado-madrid-bicentennial-exhibition (27 March 2022)

James Voorhies, ‘Francisco de Goya (1746–1828) and the Spanish Enlightenment’, The Met Museum, October 2003, https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/goya/hd_goya.htm (27 March 2022)