Peter Howson and the Bosnian War

By Kristy MacFarlane

In 1994, Peter Howson’s Croatian and Muslim, 1994, was purchased, not as expected by its initial exhibitor, the Imperial War Museum, but instead by David Bowie. This work of art was painted against a backdrop of humiliation and degradation. It was a painting borne from an experience of war that epitomised man’s degradation of mankind. Its confrontational nature, as is the case with nearly all of Howson’s work, makes it a piece of art that is inherently hard to stomach. For the Imperial War Museum, the issue was not only its horrifying subject matter, but also that the artist had not seen the event with his own eyes, making it seem deceptive. Howson had cut his time as Britain’s official war artist in Bosnia short. His artistic hand was paralysed by the sheer horror of what he witnessed. Even so, however, his partially-imagined paintings remain dowsed in un-ignorable facts and thus effectively represent a war of genocide and rape.

“In Bosnia, one day there were 150 rape victims and I had to go with these specially trained soldiers in the hills and collect them as part of a deal they had done. It was the day I lost my fear. We went into a building. It was like the degradation of humankind. Women were being raped there and then being buried underneath it in some kind of well”

Peter Howson, Croatian and Muslim, 1994, Oil on Canvas, Private Collection

http://www.artnet.com/WebServices/images/ll00209lld10MJFgVeECfDrCWvaHBOcmU8E/peter-howson-croatian-and-muslim.jpg

While this painting was not based on one single rape, it remains dowsed in truth garnered from the artist’s own experience in Bosnia. The artist’s vision is further expounded by the worrying statistic that well over 20,000 women were raped during the Bosnian conflict. The woman in this painting comes to be just one example amongst many. She is not a specific case, but an embodiment of a rape epidemic that was specifically focused on Bosniak Muslim women, an epidemic that not-so-coincidentally occurred in synchronicity with a cultural genocide that had swept through the region.

As is the case in many of Howson’s works, the male figures are presented as cumbersome and bulky; they are over-masculinised, dwarfing the woman. One man spreads the woman’s legs apart in an animalistic fashion, while the other viciously chokes her, pushing her face into a toilet. She is dehumanised. Masculinity becomes something intrinsically connected to the domination and control of women. The men that Howson depicts show their strength and virility through rape and other violent acts. The painting is claustrophobic; the composition closes in around the woman, and the viewer, much like the shadowy figure hiding behind the doorframe, is powerless as a witness. On the wall is a family portrait; this is a house where domesticity had prevailed, a peaceful sphere that has now been infiltrated by war, symbolised by the man’s rough hand clawing at the frame. Everyday life is thwarted by the bloody conflict.

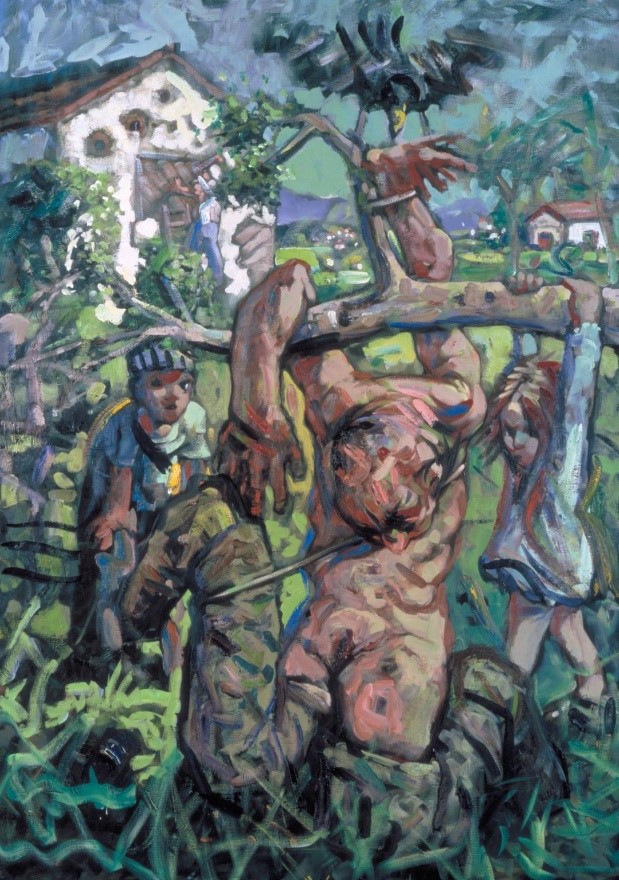

Peter Howson, Plum Grove, 1994, Oil on Canvas, Tate

http://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/howson-plum-grove-t06961

His painting Plum Grove, 1994, is also a painting that was inspired by his tenure as the official painter of the Bosnian Conflict. While this painting undoubtedly shares the same violent morbidity, it is slightly different in tone. The focal point is a dead soldier whose limbs are bent at odd angles and whose skull is penetrated by an arrow. The most striking feature of the man, however, is the fact that he has been brutally castrated. This violent and humiliating mutilation strips him of his masculinity. The effect of his broken limbs and his posture demeans and dehumanises him.

However, it is the two children in this painting that are the most troubling aspects of it. They stand in the background, looking at the mangled corpse. The boy looks intently, yet his face remains distinctly untroubled. The violent sight has become normal to him. The girl frowns, yet continues to play, hands wrapped around the very same branch from which the man hangs. They are desensitised to violence.

War conjures up images of battlegrounds and trenches, yet here it intrudes on fleeting moments of domesticity; children play with their houses just footsteps away. Everyday life is shown to go on. The sky in the background is a peaceful blue, a juxtaposition to the gruesome fore. The children continue as people continue; everyday life is built and adjusted around the horrors, until the moment it can no longer be sustained, which is presented in Howson’s Croatian and Muslim.

The woman is not just a bystander as the children are in Plum Grove; she is not a witness, but the victim. The domestic sphere of her house has been interrupted by war. Her everyday life cannot continue in the face of her rape. Croatian and Muslim becomes the symbol of what happens when war and bloodshed meet the domestic sphere. It is a painting designed to horrify. It is not a depiction of a traditional battlefield between men fighting other men. Instead, it is between two men and one outnumbered woman in a normal house, with a family portrait hanging loosely on the wall. It is emotionally challenging and disturbing as a result, and lingers in our minds as an example of perhaps the most troubling aspect of war, the death and rape of innocents. Bowie said this of the painting:

“The whole war has been cruelty and humiliation, and that is what this picture portrays. I don’t like it: I think that would be an inappropriate word, but I do think it’s very powerful and obviously very important.”

Had Bowie not bought this painting it seems likely that an American collector would have purchased it. Perhaps we should remain grateful to Bowie for ensuring that this very confrontational and disturbing piece remains in Britain for dissection and thought.

Bibliography

Jackson, Alan, A Different Man: Peter Howson’s Art, from Bosnia and Beyond, (London: Mainstream, 1997)

Heller, Robert, Peter Howson, (London: Mainstream, 1993)

Brooks, Richard, ‘Painter’s Depiction of Rape in Bosnia Deemed to Brutal for War Museum’, Chicago Tribune (October 1994) Accessed on 05/12/2017

http://articles.chicagotribune.com/1994-10-02/features/9410020406_1_imperial-war-museum-bosnian-war-croatian-and-muslim