The Theatre of David Bowie: the rebellious chameleon of the seventies

By Maria Matheos

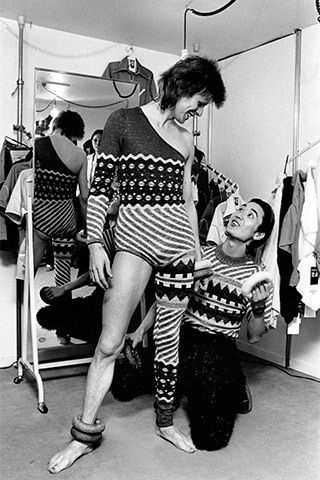

Masayoshi Sukita, David Bowie and Kansai Yamamoto, 1972. https://www.elle.com/culture/music/news/a23958/kansai-yamamoto-david-bowie-fashion-in-motion/

As a figure who was in perpetual reinvention, David Bowie’s iconic stage identities provoked and intrigued. Admittedly, there is something particularly alluring about the innovator’s Ziggy Stardust and Aladdin Sane alter egos. Not only were they the young artist’s first two personas, but they marked the development of the seventies glam rock movement, of which Bowie was a forerunner. Characterised by a rebellious attitude and an interest in the theatrical and eccentric; glam rock was an antidote to the politically and economically declining hippie climate of the late sixties. It encouraged its audience to dream of the possibilities of the future.

Bowie’s image is indebted to his collaboration with Kansai Yamamoto, the Japanese designer who crafted the costumes for Bowie’s Ziggy Stardust and Aladdin Sane tours (1972-3).

Let me begin by stating that Kansai Yamamoto is in no way blood related to the avant-garde, minimalist fashion designer Yohji Yamamoto. But he did essentially pave the way for Yohji and other designers who make up the contemporary Japanese fashion canon. Yamamoto and Bowie’s creative visions were congruous: the young designer whose unisex collection experienced success in Japan and during the London Fashion Week, found its way into Bowie’s hands after a show in 1971.

“There was a clear distinction between David ‘onstage’ and David ‘offstage.’ The second he stepped on stage, there was an immediate shift in energy, unlike that of any other artist at the time.” – Kansai Yamamoto stated, reflecting on Bowie’s performances with The Cut.

When David Bowie brought Stardust to the seventies:

In January 1972, the promiscuous and sexually ambiguous alien creature, Ziggy Stardust, of Bowie’s album, “The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars”, broke new musical ground on the Borough Assembly Hall’s stage in Aylesbury, England.This was the first, and arguably the most famous of many alter egos that Bowie would create. Featuring a one-armed and one-legged knit jumpsuit in a colourful zig-zag pattern crafted by Yamamoto, paired with a mullet haircut in a fiery orange-red hue and burgundy lipstick, Bowie as Ziggy, gave his audience the confidence to express their individuality and transcend gender boundaries.

David Bowie pictured wearing Kansai Yamamoto’s jumpsuit, during his Ziggy Stardust Tour, 1972. http://www.relics-controsuoni.com/2016/01/real-relics-6-david-bowie-ziggy-stardust-tour-1972-di-stefano-doffizi.html

For his androgynous extra-terrestrial persona, Bowie stretched over to the East, drawing inspiration from Japanese kabuki theatre, building on his interest in role-play, which had arisen from his time spent studying mime and cabaret. Striking in his ‘otherness’, Bowie also channelled the real-life country-western cult-figure, The Legendary Stardust Cowboy for his character Ziggy Stardust.

The bold and graphic asymmetrical women’s jumpsuit, designed by Yamamoto, who drew inspiration from kimono textile patterns, was met with surprise due to its image of gender-fluidity. Bowie’s stage identity was a powerfully striking collaboration between two creatives. Much like Bowie, Yamamoto had a love for the theatrical – his flamboyant costumes were based on the Japanese concept of Basara, signifying “extravagance, eccentricity and excess”.

Left: a look from Jean Paul Gautier’s ready-to-wear SS13 collection, taking inspiration from Bowie’s Ziggy Stardust, https://www.pinterest.co.uk/pin/762867624356936792/;

Right: Kansai Yamamoto, Asymmetric knit bodysuit, 1972.

https://www.thecut.com/2018/02/kansai-yamamoto-on-dressing-david-bowie-as-ziggy-stardust.html

Bowie’s and Yamamoto’s creative exchange continues to influence contemporary culture. Take a look at Jean Paul Gaultier’s ready-to-wear SS13 collection, Rockstars, featuring models in shocking red mullets and asymmetric patterned jumpsuits. It is a re-imagination of Bowie’s Ziggy Stardust.

“People didn’t understand that you didn’t have to be the same personality every time you went on stage” – David Bowie, 1977.

A-Lad-utterly-Insane

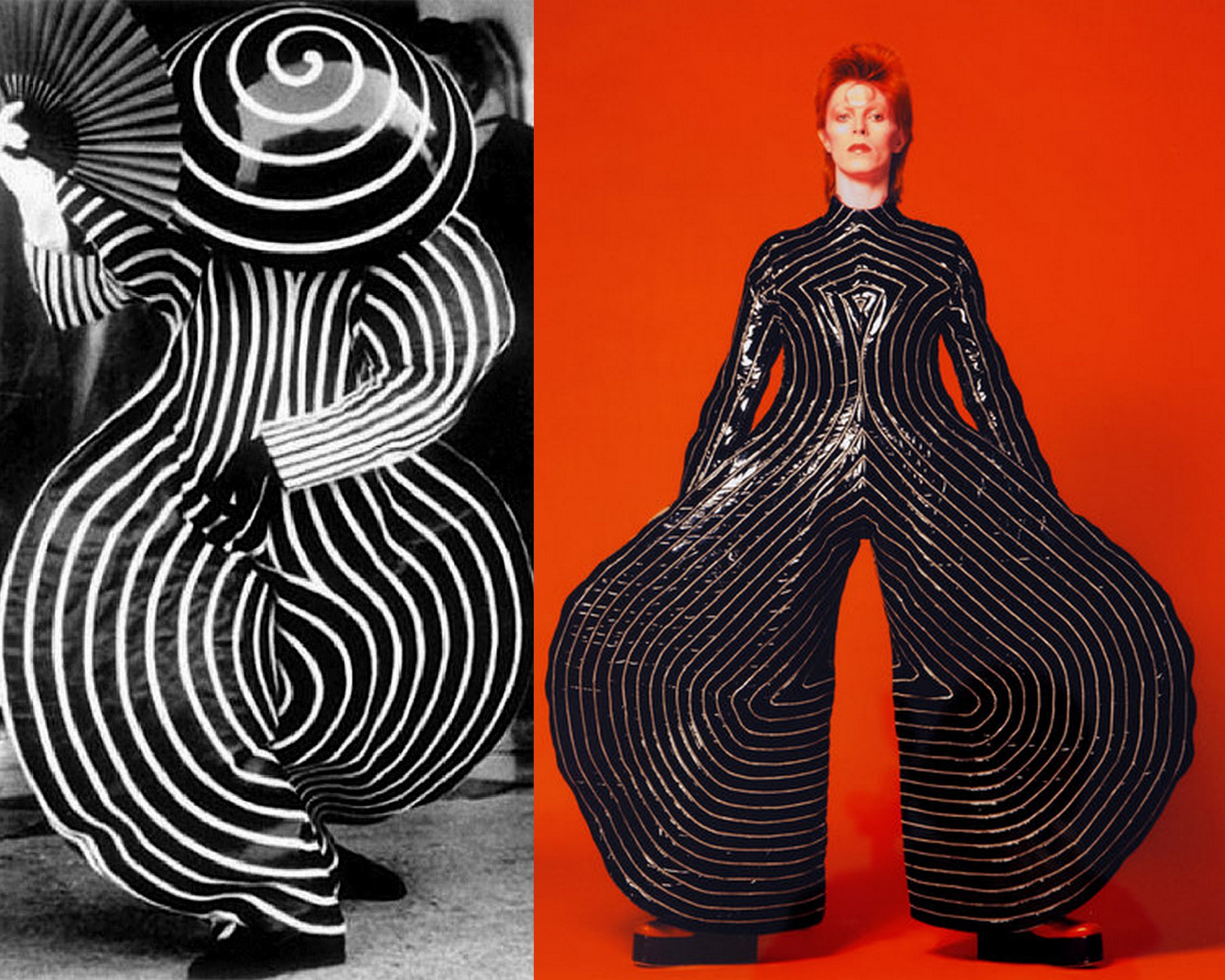

Three months later Ziggy no longer played guitar: Bowie had metamorphosed into Aladdin Sane. Parading across the stage in red platform boots and a patent-leather black and white balloon leg jumpsuit, referred to by designer Yamamoto as the ‘Tokyo pop’ jumpsuit, Bowie sought to assault the senses of his audience. Completely over the top? Yes. Verging on a parody of excess? Possibly. Would he have wanted us to take him seriously? He certainly did not (take himself seriously).

With Aladdin Sane, Bowie gave us a hyperbolic extension of his prior alien doppelganger; adding that his character, a pun on ‘A Lad Insane’, represented “Ziggy under the influence of America”.

Left: Oskar Schlemmer, Costume from Das Triadisches Ballett, 1922, https://www.are.na/block/876938%20/;

Right: Masayoshi Sukita, David Bowie wearing Kansai Yamamoto’s Tokyo pop jumpsuit, 1973. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2018/03/20/arts/design/bowie-costumes-ar-3d-ul.html

Yamamoto’s sculptural costume, designed for Bowie’s 1973 tour, unsnapped along the sides and sleeves to allow for quick costume changes onstage – an element of surprise borrowed from kabuki theatre. The exaggerated silhouette is reminiscent of the Bauhaus artist and choreographer, Oskar Schlemmer’s optical costumes for his 1922 ballet Das Triadische. Schlemmer’s ballet costumes reflect his interest in geometry: their heavy and stiff architectural structure transform the human body into a geometric and formalist shape. Playful and humorous, the costumes sought to blur the boundaries between architecture, pantomime and dance, in a similar way to Bowie’s melding of multiple forms of performing arts.

Brian Duffy, Aladdin Sane cover shoot, 1973. https://www.anothermag.com/art-photography/8162/flash-of-genius-photographing-aladdin-sane

The cover of Bowie’s Aladdin Sane album, shot by Brian Duffy, has become somewhat of a reference point for the artist in contemporary popular culture. It has certainly featured on my pin board since Bowie’s retrospective at the V&A in 2013. Striking in its simplicity, Bowie is captured with a blue and red lightning bolt painted across his face, but that does not detract from his trade-mark, shocking flame-coloured hair. Was Bowie’s lightning bolt an external manifestation of his inner tension as the pressure of keeping up his creations proved to be stressful? This is what the media suggested, and, of course what everyone believed. Much to their dismay, and our amusement, Bowie stated that the lightning bolt was borrowed from the logo of his studio kitchen’s rice cooker. How anti-climactic.

Aladdin Sane was reborn as Halloween Jack a year later.

As the unpredictable performer and innovative designer of their generations, David Bowie and Kansai Yamamoto adopted a Dadaist approach, cutting up and stitching together fragments to create looks that were theatrical and avant-garde. While Bowie certainly drew inspiration from others, his own importance as a cultural icon is indisputable. He changed the face of fashion and performance; encouraging experimentation and gender-fluid dressing. Most importantly, he urged us to take action: his eccentric creations serve to remind us that everything is constructed, and therefore can be reconstructed – quite a Brechtian sentiment.

Bibliography

Dellas, Mary.“Dressing David Bowie As ‘Ziggy Stardust’”, The Cut, February 26, 2018. Accessed 25 February 2019. https://www.thecut.com/2018/02/kansai-yamamoto-on-dressing-david-bowie-as-ziggy-stardust.html

Elliott, Mark. “Children of the Revolution: How Glam Rock Changed the World”, Udiscovermusic, October 17, 2017. Accessed 25 February 2019. https://www.udiscovermusic.com/in-depth-features/how-glam-rock-changed-world/

Ginsberg, Merie. The Japanese Designer Who Helped Turn David Bowie into Ziggy Stardust Speaks, The Hollywood Reporter, 16 March 2016. Accessed 25 February 2019. https://www.hollywoodreporter.com/news/japanese-designer-who-helped-turn-875547

Ryzik, Melena. “Augmented Reality: David Bowie in Three Dimensions”, The New York Times, 20 March, 2018. Accessed 25 February 2019. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2018/03/20/arts/design/bowie-costumes-ar-3d-ul.html

Ryzik, Melena. “The Bowie You’ve Never Seen”, The New York Times, 19 March, 2018. Accessed 25 February 2019. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2018/02/27/arts/music/david-bowie-is-brooklyn-museum-exhibit.html

Sheffield, Rob. “How America Inspired David Bowie to Kill Ziggy Stardust with Aladdin Sane”, The Rolling Stone, April 13, 2016. Accessed 25 February 2019. https://www.rollingstone.com/music/music-news/how-america-inspired-david-bowie-to-kill-ziggy-stardust-with-aladdin-sane-230827/