'Something Crazy Special': Charlotte Salomon's painting of life and destruction

By Eilís Doolan

The art of Charlotte Salomon has been surprisingly absent from the story of art history. In fact, her name is barely known outside of small circles. I only became aware of her work around a week before I started writing this. Yet, I feel confident, after only a few days of research, that Salomon’s art is complex and incredibly compelling. First brought to public attention in 1961, years after her death in Auschwitz at age 26, Salomon’s life work is comprised of a collection of 769 small gouaches overlaid with text, forming a work titled Life? Or Theatre? The paintings, all completed between 1941 and 1942, were selected by Salomon herself from a total of 1299 paintings, 340 overlays of text, and 32’000 words—a strikingly large oeuvre completed within only one year. The selected paintings are organised into three parts, namely the prelude, main part, and epilogue. Salomon’s Life? Or Theatre? defies all attempts at categorization, presenting a visual record of her life, developed by genre scenes and portraits, featuring a cast of characters which are simultaneously fictional and real.

Salomon’s life work is both complex and difficult. Treading the line between fiction and autobiography, it is tempting to read Salomon’s work as an example of “Holocaust art.” Yet, most pages of Salomon’s Life? Or Theatre? are not about the Holocaust at all. Instead, the majority of her gouaches are concerned with daily life, family tensions, and desires. Simon Schama, indeed, has referred to the work as a “domestic opera of sensual manoeuvre.” Salomon herself referred to her work as “something crazy special.” Undoubtedly, Life? Or Theatre? presents a compelling reflection of the experience of a woman navigating life in a darkly troubled family.

One of the paintings of Nazi Germany, depicting 30 January 1933, when Hitler is named chancellor of Germany. Photograph: Charlotte Salomon Foundation

Born in 1917 Berlin, Salomon’s financially privileged childhood was plagued by depression. Over three generations, her family suffered the suicides of two men and six women. Salomon herself was named after her mother’s only sister, who drowned herself at the age of 18. When Salomon was eight, her mother fell into severe depression, leading her to jump from a window just a year later. Images referring to her mother’s suicide appear frequently in Salomon’s work, reflecting a preoccupation with the self-destruction of women in her family. In one painting, a mother lies in bed with her daughter, and asks if it would be nice if Mummy became an angel. In another, the mother explains: “in heaven, everything is much more beautiful than here on earth.” A further picture depicts Charlotte waking ten times a night to see if the angel of her mother has visited her at her window. The text accompanying the picture reads: “she is very disappointed.”

Painting depicting Franziska telling her daughter: In Heaven everything is much more beautiful” and depicting the young Charlotte waiting for the angel of her mother to arrive at the window. Photograph: Jewish Historical Museum, Charlotte Salomon Foundation

By the time that Hitler was appointed chancellor of Germany, Salomon’s father had married singer Paula Lindberg, referred to as Paulinka Bimbam in Salomon’s work. Salomon attended the Academy of Arts in Berlin, even receiving first prize in a blind competition during her second year – after she was revealed as the artist of the winning work, the award was swiftly given to another, non-Jewish, student. In the 1930s, Salomon’s stepmother hired a vocal coach named Alfred Wolfsohn, with whom Salomon quickly became enamoured and started a love affair. Wolfsohn, referred to in Salomon’s paintings by the fictional name Amadeus Daberlohn, features prominently in Life? Or Theatre?, acting both as an object of desire as well as a source of inspiration and hope.

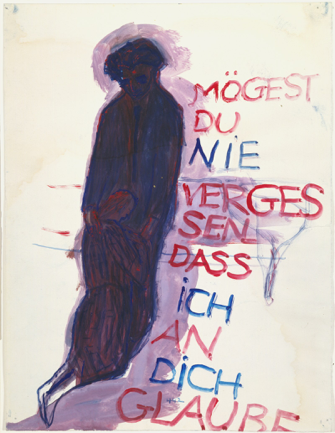

Daberlohn says to Charlotte: „May you never forget that I believe in you.“ Photograph: Jewish Historical Museum, Charlotte Salomon Foundation

After Kristallnacht, Salomon’s father and stepmother fled to Amsterdam, while she was sent to live with her grandparents in Villefranche on the Cote d’Azure. Several paintings in Life? Or Theatre? depict Charlotte’s emotional final meeting with Daberlohn. In 1939, Salomon’s grandmother attempted to commit suicide by hanging herself in a bathroom. Later, after a move from Villefranche to Nice, Salomon’s grandmother succeeded in killing herself, leaping from a window as her daughter had 14 years earlier. Charlotte witnessed the event. In the following years, after narrowly avoiding a nervous breakdown, Salomon followed her doctors’ advice and began to paint, creating an astonishing total of 1299 paintings about her life. Of the dead women in her family, Salomon writes: “I will live for them all. I became my mother, my grandmother.” Now, Salomon was the only surviving heir to the family.

In 2011, a discovery afforded art historians a further glimpse into who Charlotte Salomon was; In 1943, just eight months before her own death, Salomon murdered her own grandfather, likely as the result of continued abuse. Salomon documented the murder in a 35-page confession letter, which was kept hidden by family for more than 60 years. Fragments of the letter were first made public in a 2011 documentary, and then released in its entirety in 2015 by the Parisian Le Tripode. In it, Salomon writes: “I know where the poison was. It is acting as I write. Perhaps he is already dead now. Forgive me.” The letter describes that Salomon drew her grandfather’s portrait as he died. A surviving ink drawing depicts an old man with closed eyes and a slumped head.

In 1942, with the war escalating, Salomon wrapped up her paintings, placed them in packages, and brought them to her doctor for safekeeping. A year later, on October 7th, 1943, Salomon and her husband were arrested by the Gestapo. After three days of travel, Salomon was gassed upon arrival at Auschwitz—she was 26 years old and five months pregnant. In 1947, her paintings, hidden away in a basement in Villefranche, were discovered by her father and stepmother. They were unaware their daughter had ever painted a single image.

Since her work was first made public in a 1961 exhibition at the Jewish Historical Museum of Amsterdam, Salomon’s paintings have often been read simply as reflecting the experience of a victim of the Holocaust. Early commentaries referred to her only by first name, perhaps in a misguided attempt to market her as an accompanying figure to Anne Frank. What has furthered this interpretation is the fact that Salomon’s parents were close friends with Otto Frank – both families found themselves tasked with the question of what to do with the artistic legacy of their daughters. Yet, more recently, art historians have pushed for a different reading of Salomon. Griselda Pollock, who has studied Salomon’s works for over 20 years, has called for the separation of Salomon’s work from the category of “Holocaust art.” In fact, Pollock argues that this reading has held Salomon’s work back, ultimately leading to her absence from the canon. Thus, in order to push for a wider awareness and understanding of Salomon’s work, it is the task of art historians and journalists alike to move beyond the reading of Salomon as a tragic figure or heroic artist whose art serves to comfort the viewer. Instead, Pollock states: “It doesn’t comfort us. It is a fearless engagement with the question of crime and violence and suffering.” Salomon’s Life? Or Theatre? is a remarkable example of an artist who adopted a range of techniques to create a visual narrative of both joyful and dark moments in her life, including small vignette formats, stationary portraits, energised lines, and the incorporation of text. In a sense, her paintings prelude modern graphic novels. Most importantly, however, Salomon’s work forms a modernist masterpiece – a story of women’s self-destruction. In the end, artistic creation seems to serve both as a record of self-destruction and a tool with which to overcome it.

‚Dear God, please don’t let me go mad’ Photograph: Jewish Historical Museum

The full pages of Charlotte Salomon’s Life? Or Theatre? can be found on the website of the Jewish Historical Museum under the following link: https://charlotte.jck.nl/part/character/theme/keyword

Bibliography

Bentley, Toni. “The Obsessive Art and Great Confession of Charlotte Salomon.” The New Yorker. Published 15 July 2017. Accessed 20 December 2019. https://www.newyorker.com/culture/culture-desk/the-obsessive-art-and-great-confession-of-charlotte-salomon?verso=true.

“Charlotte Salomon. Leven? Of Theater?” Joods Cultureel Kwartier. Accessed 26 December 2019. https://jck.nl/nl/tentoonstelling/charlotte-salomon-leven-theater

Jones, Jonathan. “A Spirit the Nazis Couldn’t Erase: Charlotte Salomon: Life? or Theatre?” Guardian. Published 6 November 2019. Accessed 20 December 2019. https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2019/nov/06/charlotte-salomon-life-or-theatre-review-jewish-museum-london-graphic-autobiography

Joods Cultureel Kwartier. “Charlotte Salomon’s ‘Life? or Theatre?’” YouTube video, 02:05. Posted 8 January 2018. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=F9wRMQ81Y_g.

Joods Cultureel Kwartier. “Interview Paula and Albert Salomon for Pariser Journal, 1963.” Filmed 1639. YouTube video, 06:15. Posted 25 March 2015. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NlytljkojGo.

Schama, Simon. “Charlotte Salomon at the Jewish Museum London – Simon Schama on a modernist masterpiece.” The Financial Times. Published 13 November 2019. Accessed 21 December 2019. https://www.ft.com/content/97e00f90-0484-11ea-9afa-d9e2401fa7ca.

YaleBooks. “Griselda Pollock discusses the life and work of artist Charlotte Salomon.” YouTube video, 07:24. Posted 12 February 2018. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mGVtJydKHgo.