Nihon no Hanga: Exploring the Rijksmuseum's Für Elise Foundation and Japanese Twentieth Century Prints

By Dawn Lui

As the largest collection of Johannes Vermeer’s works was unveiled at the Rijksmuseum in February, the museum in Amsterdam once again became an even hotter name for art enthusiasts on their Netherlands bucket list. Hidden underneath the Main Hall and Library, under a winding staircase, stands the Asian Pavilion—small, but packed with collections of South and East Asian prints, sculptures, and decorative arts. Among those stood the largest collection of Japanese prints gifted by the Für Elise Foundation to the museum in October 2022. Given the Dutch fascination with the East ever since the Dutch East India Company in the seventeenth century, Japanese aesthetics have enriched the Holland’s art history. Therefore, when visiting The Rijks for Vermeer, spare some time to admire the Nihon no Hanga collection. Its splendid liminal blend of old and new aesthetics trail-blazed the first waves of Pre and Post War Japanese modernism. Therefore, it surely deserves attention next to the many European Old Masters.

Author’s Own Image

Having visited the museum myself during the winter break, the presentation and subject matter of these prints proved intriguing. The incorporation of modern and traditional techniques and subjects is almost seamless, presenting temporally non-existent pieces of abstract Japanese nostalgia. Despite a history of Japanese print donations to the Rijksmuseum dating back to 1902, including pieces by Hokusai, Utamaro and Hiroshige, the Nihon no Hanga collection remains a shining spot within the institution with its own spark. These prints, created by a collective of artists throughout the 1920s and 40s were categorized as a new wave from the ancient Ukiyo-e woodblock printing style. The Nihon no Hanga collection includes two major neo-Ukiyo-e styles: the Sōsaku-hanga (創作版画)and the Shin hanga (新版画); translated to ‘creative prints’ and ‘new prints’ respectively. To understand these print’s influential status, one must acknowledge the technique, history, and revival of these styles.

The Sōkasu Hanga welcomed its revival ever since the two-century long influx of European Ukiyo-e reproductions in 1907. The art magazine, Hosun, published in year forty of the Meji era popularised the style with its distinct vibrant colours and lithographs. By the beginning of the Taisho period in the early to mid twentieth century more experiments were made to match with the rapidly reforming and modernising nation. The craze of Sōkasu Hanga eventually prompted the establishment of the Nippon Sōkasu Hanga Kyokai society, gathering and curating exhibitions that merges the Shin and Sōkasu Hanga styles with vibrant and decorative Katagami stencils. Used originally as a fabric printing technique on everyday wear, the Katagami made its way into works of Utamaro and Hiroshige that enriches the lavish lifestyles of the men and women in their portraiture.

Kiyoshi Kobayakawa, Lip Rouge, Elise Wessels Collection

In Lip Rouge, Kiyoshi Kobayakawa (小早川清) showcases his masterful Katagami technique through the subject’s decorated Kimono and makeup mirror. Despite his traditional formatting of Ukyo-e Bijin-ga (美人画) (portraiture of beautiful women), he emphasizes her ‘beauty-enhancing’ possessions. From the ruby ring on her right hand facing the audience, to the bullet lipstick she is applying to her lips, they present a stark clash between the ancient Japanese technique and modern Western products. The depiction of these modern cosmetics in their own two-dimensional Ukiyo-e aesthetic is a declaration of the ‘new woman’ of Japan. A new femininity that embraces their own heritage while striving for modernisation and coexistence between Western and Eastern cultures.

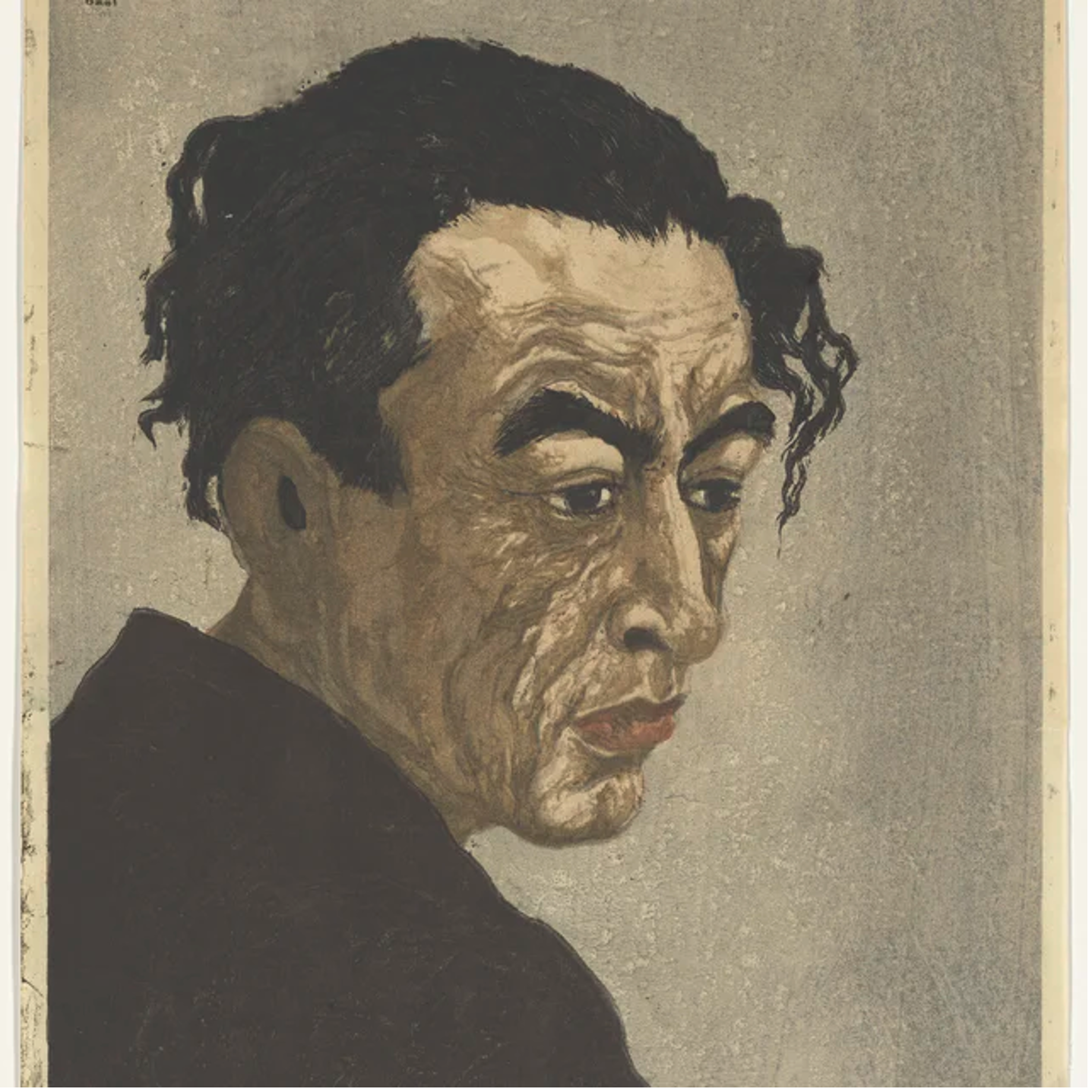

After World War II, which resulted in an economic, and environmental disaster as the nuclear bomb dropped at Hiroshima and Nagasaki on 6th August 1945, the Sōsaku Hanga style underwent drastic transformation. By the end of the 1940s, Sōsaku Hanga prints challenged their traditional techniques, style and formation as a way to interrogate life after trauma and death. In Onchi Kōshirō’s portraiture of Hagiwara Sakutarō, the Ukiyo-e’s characteristic vibrant colours were abandoned. Instead, muted earth tones make up the palette of this Sōkasu Hanga. Its lithographic carving techniques were used to enhance the sitter - Hagiwara’s - skin texture and shadows, rendering the custom of smooth, two-dimensional faces of Ukiyo-e prints obsolete. Kobayakawa’s realism and use of colour represented the bleak minds of many Post-War Japanese. At the beginning years of McCarthyism, the Japanese begin to challenge their identities as a nation. Rapid Westernisation comes to a screeching halt in the 1930s into heated patriotic militarism, then descends into its rejection during the times of budding communist ideologies and eventual control of the McCarthyistic government in the late 40s. The constant upheaval of social revolution and Post-War trauma seeps into the prints of Onchi Kōshirō, stripping bare the characteristics of the Ukiyo-e, screaming his question as loud as bleak his colours can be—who are we now?

Onchi Kōshirō, Portrait of Hagiwara Sakutarō, 1949, Gift from the Für Elise Foundation to the Nihon no Hanga Collection.

Notes:

Brown, Kendall H. “Out of the Dark Valley: Japanese Woodblock Prints and War, 1937-1945.” Impressions, no. 23 (2001): 64–85. https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/42597893.pdf?refreqid=excelsior%3Ab3c6449efb238f946fd93fd6d1214d7c&ab_segments=0%2Fbasic_search_gsv2%2Fcontrol&origin=&initiator=&acceptTC=1.

Nihon no Hanga Collection. “Nihon No Hanga.” Nihon no Hanga. Accessed March 24, 2023. https://www.nihon-no-hanga.nl/?page_id=13.

Onchi, Koshiro. “THE MODERN JAPANESE PRINT - an International History of the Sosaku‐Hanga Movement.” 浮世絵芸術 11 (1965): 3–24. https://doi.org/10.34542/ukiyoeart.146.

Rijksmuseum.nl. “Rijksmuseum Receives Largest-Ever Gift of Japanese Prints - Rijksmuseum,” October 12, 2022. https://www.rijksmuseum.nl/en/press/press-releases/rijksmuseum-receives-largest-ever-gift-of-japanese-prints.