The Window and the Mirror. A Duality of the Soul in Sylvia Plath's Painted and Poetic Portraits.

By Isabelle Holloway

The self often appears caught between two opposing ‘window’ and ‘mirror’ worlds in the work of American writer Sylvia Plath: the former describing the reality of external conditions, while the latter exemplifies the subjectivity of internal experiences. Aligned with the intentions of her early painted body of work, Plath relates this window-mirror concept to photographic portraits, describing them as follows:

“Photograph-portraits do catch our souls – part of a past world, a window onto the air and furniture of our own sunken worlds, & so too the mirror twin, Muse.”

The art of pictorially capturing the soul, however, is not confined to photography; art forms like poetry and painting also offer the opportunity to fashion versions of the “past” or “sunken” worlds she describes. Her explorations of these themes vary across her painted and poetic abstractions - through which we can gaze metaphorically upon her own self-reflexive ‘window-mirror’ to the soul, often amplified by literary accompaniment in the form of poetry.

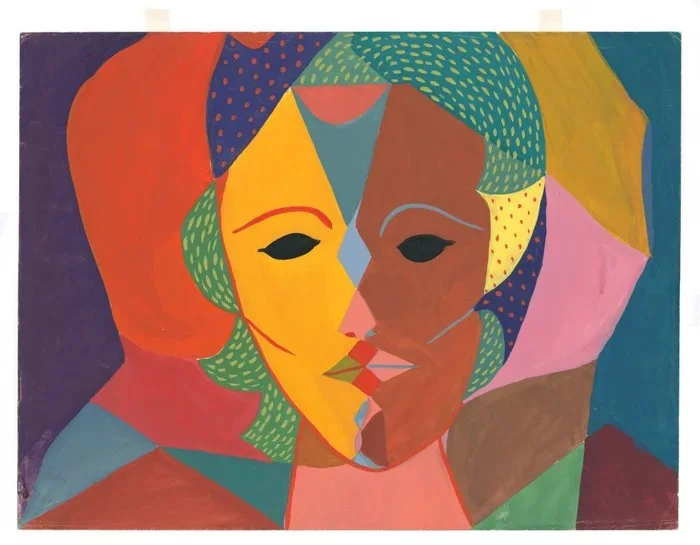

Figure 1: Sylvia Plath, Triple-Face Portrait, 1950-1951, tempera on paper, The Lilly Library, Indiana University Bloomington, Indiana.

Plath’s senior thesis, The Magic Mirror: A Study of the Double in Two of Dostoyevsky’s Novels, analyses the literary theme of the ‘double,’ describing the phenomenon as “the evil or repressed characteristics of its master.” Visually, through the stark and vibrant simplification of sharpened shapes, we can see Plath grappling with themes of the double, or indeed, triple in the fragmented or mirrored aspects in her Triple-Face Portrait (fig. 1). Her contemporary literary works similarly play with this concept. The Bell Jar (1963), a thinly veiled semi-autobiographical novel, centers around an ambitious and accomplished young woman, who like Plath, is caught in the throes of inner turmoil and self-destructive tendencies. The poems, “Tulips” and “Lady Lazarus” navigate in parallel similar themes of existential duality – beauty and destruction; control and chaos; life and death. Likewise, Plath’s personal Journals shed light on her sincere struggles to balance daily duties with self-expression: duty as a student, wife, and mother -- and self-expression, as deeply creative, though tormented, artist and writer.

Plath’s melancholic artistic identity has been heavily mythologised following her untimely death, the subject of her writings and artworks having unfolded in conjunction with her own struggle with mental illness. Posthumously, the “Sylvia Plath Effect” posits an increased susceptibility of poets to depression, eponymous with the artist-writer’s gripping documentation of her lived experience. Her writing, subsumed by its dark legacy, has therefore often consoled or spoken to those trapped under their own ‘bell-jars;’ her portraits capturing a sense of living grief, evocative of the experience of depression.

Plath’s identity, however, extends beyond the reach of her ultimate tragedy. As a writer, her eye for detail, appreciation for sensory stimuli, and obsession with literary perfection began with an initial passion for the visual arts. In high school, Plath’s participation in art classes, clubs, and private lessons led her to initially pursue studio art, rather than English, at Smith College. As a college student, she enjoyed visiting art museums and studying academic literature on paintings, volunteering weekly to teach art to children.

Her affinity and emulation of the early European avant-gardes featured evidently across her artworks in the form of stylistic inspirations, experiments, and citations. Whilst auditing a course on modern art when she returned to teach English at her alma mater, Plath would have been introduced to the Cubist and Surrealist movements, and even wrote poems dedicated to Henri Rousseau’s The Dream and Giorgio de Chirico’s The Disquieting Muses. Surrealist themes of the dream, and at times the uncanny – each evident in these two portraits paintings – alludes the alienation, otherworldliness, and dark symbolism present as thematic inspirations in Plath’s poetry collection Ariel.

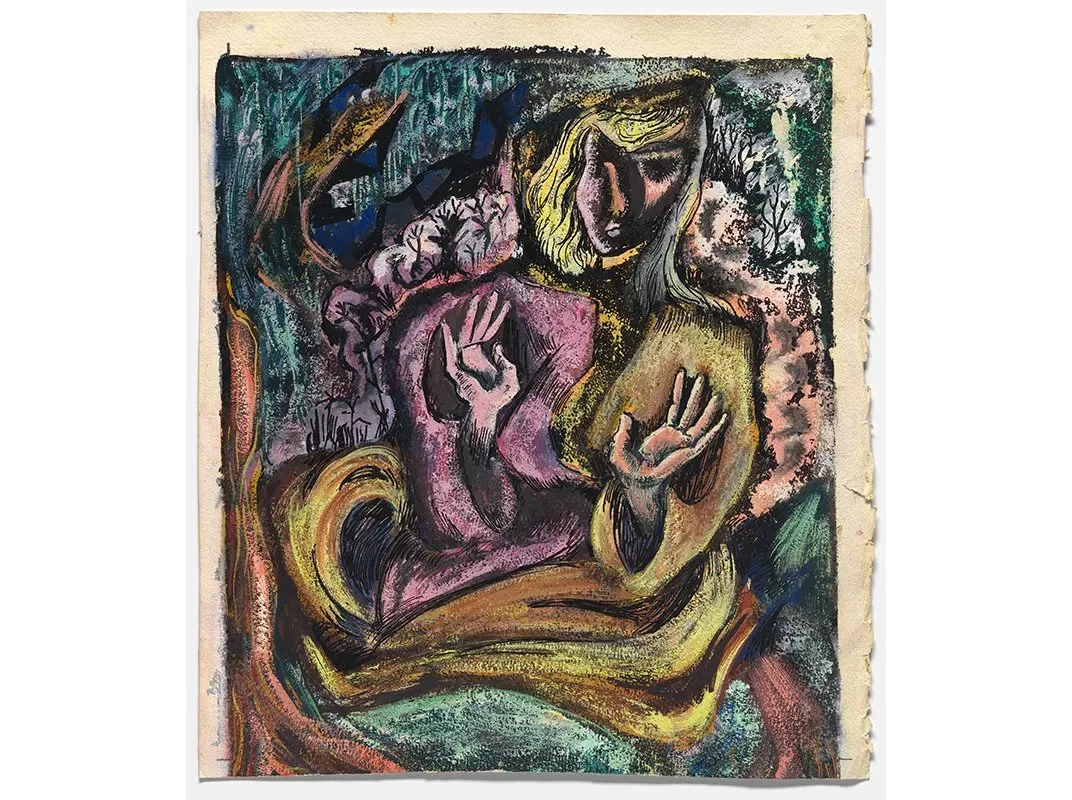

Plath’s poetic themes and visual art converge along this window-mirror axis of her world, as exemplified in her Triple-Face Portrait and Self-Portrait in Semi-Abstract Style (fig. 2). The window of Plath’s societal and personal expectations intersects with the mirror of her psychological facets, capturing her multi-dimensional, human experience.

Figure 2: Sylvia Plath, Self-Portrait in Semi-Abstract Style, 1946-1952, ink and gouache on paper, Estate of Robert Hittel.

The geometric fragmentation of Triple-Face Portrait portrays Plath as an ambiguous puzzle. On one hand, the painted fragments “break up in pieces that fly about like clubs,” (from her poem Elm); on the other, they hold “colours cruelly locked in hexagonal hearts of ice” by “omnipotent white frosts.” Enshrined by the darkness of her own poetic descriptions, Plath’s Triple-Face Portrait creates a juxtaposing jigsaw of chaos, control, and calm. In this pair of portraits, Plath realises a “bleak and geometric tension,” trapping “the individual in the cell of her own limitations.” By applying tempera into the neat line-work of such segments, Plath can be seen concealing and revealing her own compulsive need to fulfill her ascribed societal roles, whilst grappling with opposing spiritual and internal worlds. Yet, the imperfect textures and riot of colour suggest an implicit vulnerability; perhaps that of her ‘inner child,’ reflecting with tentative hopefulness, the artist’s acknowledgement that she “must bridge the gap between adolescent glitter & mature glow” toward healing. Plath’s practically unattainable “desire to be many lives,” alluded to further in her fig tree metaphor – wherein all figs shrivel amidst overwhelmed indecision - is pictorially actulised via the separated blocks of colour of her self-portraits.

Signifying her internal struggle with dark thoughts, in Plath’s own words, “the colours locked into the all-comprehensive blackness.” If eyes are windows to the soul, then Triple-Face Portrait with its solid onyx eyes unlids Plath’s inner darkness in the “black amnesias of heaven” that are her eyes. Protagonist Esther reflects similarly in The Bell Jar, “I shut my eyes, and all the world drops dead.” Evident in the tone of both portraits, Plath’s internal ‘mirror’ and dehumanising psychiatric experiences made her feel reduced to a “bundle of past recollections and future dreams” all “knotted up.” In The Rabbit Catcher poem, much like her Self-Portrait in Semi-Abstract Style, “the wind gag[s] [her] mouth with [her] own blown hair.” Plath’s painted and poetic imagery powerfully evokes this Rapunzel-esque imagery of entrapment through the visual iconography of tendrilous, blonde hair. Her belief, that “being born a woman is my awful tragedy,” tethering her long hair with the price of femininity in her male-dominated society.

Plath’s Self-Portrait in Semi-Abstract Style captures the warping sensations of staring into a mirror for too long. The line forms sway haphazardly like “a jigsaw puzzle of high tight clouds,” yet with a boundless relief: “God, it was good to let go, let the tight mask fall off, and the bewildered, chaotic fragments pour out.” Her upturned hands in Self-Portrait are both eerie and reflective: her poem “Tulips” expresses that “I only wanted / To lie with my hands turned up and be utterly empty,” conveying an empty exhaustion of the soul. The scratchy bundles of forest, its “trees receded […] like the dark sides of a tunnel,” from The Bell Jar, further shades Plath’s world with desolation. An empty sky recalls Plath’s journal entry and her lifelong disillusionment with faith, writing, “I talk to God, but the sky is empty.” Yet, the yogic composure of Plath’s hands also exudes peace and serenity. Esther expresses in The Bell Jar: “I felt my lungs inflate with the onrush of scenery— [...] I thought, ‘This is what it is to be happy.’” Thus, the swirling, compositional unity of Plath’s self-portrait also reveals her genuine joy for life.

Through this pair of self-portraits, Plath asserts that she is not a martyr, but a human being. Her Journals paint her as a woman who was both divinely unique and compellingly relatable: she loved sherry, hot baths, and the occult; got drunk at Parisian bars, went on dates with boys, and splurged on the latest fashions; and was as witty as she was unrelenting. Importantly, Plath proved herself as a gifted artist, with or without death to consecrate her. By immortalising her outer ‘windows’ and inner ‘mirrors’ into writing and visual art, Plath was able to assert her hidden resilience — one that resounds in the “old brag” of Esther’s heart — and which drove Plath, in her own words, to make “beauty out of sorrow”.

Bibliography:

Academy of American Poets. “What Sylvia Plath Loved.” Poets.org. https://poets.org/text/what-sylvia-plath-loved.

Brockman, Maria Popova. "Sylvia Plath's Drawings: A Visual Reflection of Her Inner World." The Marginalian, June 14, 2012. https://www.themarginalian.org/2012/06/14/sylvia-plath-drawings/.

Browne, Allen C. "Sylvia Plath." Allen C. Browne's Blog, August 4, 2017. http://allencbrowne.blogspot.com/2017/08/sylvia-plath_4.html

Doomchin, Sarah. "The Art of Sylvia Plath's Doom." Writing Program Journal, Issue 9 (n.d.). https://www.bu.edu/writingprogram/journal/past-issues/issue-9/doomchin/

Gordon, Joan. "Sylvia Plath’s Undergraduate Thesis and the Doppelgangers of The Bell Jar." The Atlantic, May 21, 2018. https://www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/2018/05/sylvia-plaths-undergraduate-thesis-the-bell-jar-doppelgangers-doubles/560540/.

Harris, Elizabeth. "Sylvia Plath: A Life in Art – in Pictures." The Guardian, July 1, 2017. https://www.theguardian.com/books/gallery/2017/jul/01/sylvia-plath-art-photographs-national-portrait-gallery.

Katz, Brigit. "The Whimsical, Chameleon Figure Behind the Myth of Sylvia Plath." Smithsonian Magazine, September 16, 2020. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smithsonian-institution/whimsical-chameleon-figure-behind-myth-sylvia-plath-180963831/.

Lapham’s Quarterly. “Sylvia Plath’s Reading List.” Lapham’s Quarterly. https://www.laphamsquarterly.org/roundtable/sylvia-plath-reading-list.

Lazzaro, Caterina. "The Art of Sylvia Plath." Daily Art Magazine, September 18, 2020. https://www.dailyartmagazine.com/art-of-sylvia-plath/.

Literary Ladies Guide. "Fascinating Facts About Sylvia Plath." Literary Ladies Guide. https://www.literaryladiesguide.com/literary-musings/fascinating-facts-about-sylvia-plath/.

Plath, Sylvia. Ariel: The Restored Edition. Edited by Frances McCullough. New York: HarperCollins, 2004.

Plath, Sylvia. The Bell Jar. New York: Harper & Row, 1971.

Plath, Sylvia. The Unabridged Journals of Sylvia Plath. Edited by Karen V. Kukil. New York: Anchor Books, 2000.

Reed, Tori. "Sylvia Plath’s Art Is a Rare Look at Her Full, Complicated Self." Vice, December 14, 2022. https://www.vice.com/en/article/sylvia-plath-retrospective-visual-art-smithsonian/?utm_source=tcpfbus.