Elizabeth Siddal as Herself: Artist, and Muse.

By Eden Binjaku

Elizabeth Eleanor Siddal (1829-1862): artist, poet, and muse, is most widely recognised as Millias’s Ophelia and Rossetti’s Beatrice. The portrayals of Siddal as romanticised yet tragic literary figure merged with her real life struggles, poor health, and untimely death. Considering she was the only woman exhibited at a 1857 Pre-Raphaelite exhibition, scholars have sought to reframe understanding of the muse by recognising her own artistic aspirations and relationship with the Pre-Raphaelite movement.

The story of Siddal becoming very ill after posing as Ophelia (fig.1) in a cold bathtub became a part of the “foundation myth” for the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. Furthermore, it created a lasting myth of Siddal as a devoted art-model with an elusive and tragic nature that merges with her literary counterparts. After modelling for a few other members of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, Siddal became the exclusive muse of Dante Gabriel Rossetti, with whom she had a years-long courtship and short marriage.

Figure 1: John Everett Millais. Ophelia. 1852. Oil on Canvas. 30x44. Tate Britain.

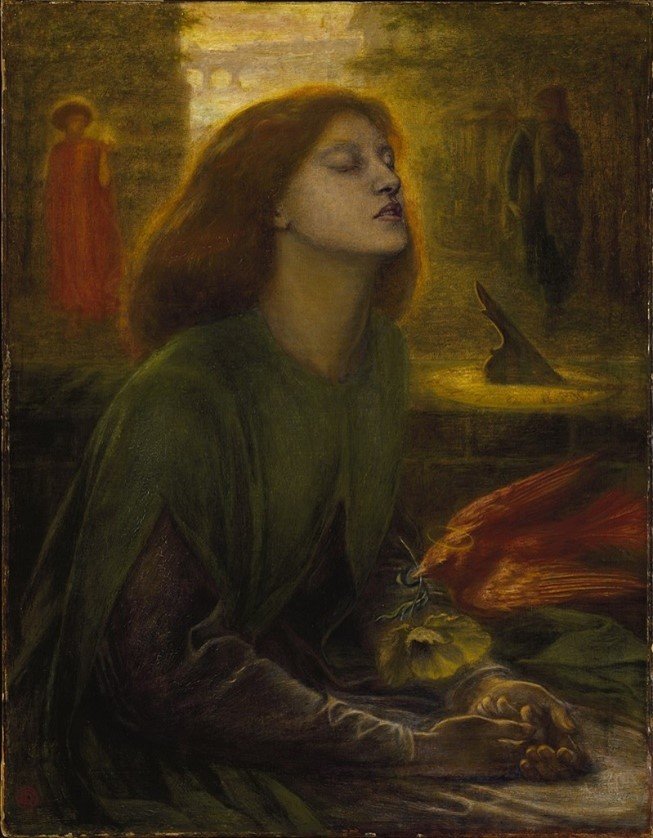

Based on drawings of Siddal while she was alive, he depicts her receiving a white poppy (related to her laudanum overdose) from a red dove. The parallels with the relationship of Dante and Beatrice, up until the spiritual nature of the inspiration she evokes, are highlighted in this work. It is significant that Rossetti probably utilised an amalgamation of private drawings of Siddal done while she was alive. This not only makes it a reflection on the blurred line between memories, life and death, but also between the “real” Elizabeth Siddal, and the “Beatrice” which Rossetti transforms her into.

Figure 2: Dante Gabriel Rossetti. Beata Beatrix. 1872. Oil on canvas, 85.7x67.3cm. Tate Britain. London.

In fact, it was not until after the death of Rossetti that Siddal began to be written about. For example, his brother, W. M. Rossetti wrote the first account of her life in 1903. He describes her humble beginnings, introduction into the Pre-Raphaelite circle, relationship with Dante Rossetti, and, most significantly, her talents in art and poetry. The former, which were recognised even by John Ruskin (her benefactor), and presented at exhibitions. While commemorative and empathetic, W.M.R. admits to knowing little of her as an individual, and the recollections are shaped by her importance to his brother.

Long repeated accounts of Rossetti’s grief and guilt following her death, especially of him burying his poetry with her, and later exhuming the grave to retrieve the manuscript for publication leave lasting impressions of him as a romantic poet/artist, overcome by an elusive supernatural female figure.

Inescapably, a sense of Elizabeth Siddal’s identity was merged with poetic and literary allusions. This is not only due to the interests of the Pre-Raphaelites, which involved nature, romanticism, medieval ballads, quattrocento art, literature and spirituality. It also reflects the Victorian obsessions with ideal femininity, female melancholy/madness, and the “cult of death.” With this context, it is not a surprise that those aspects of Siddal, and the characters she is painted as, left a lasting impression.

Elizabeth Siddal’s Self-Portrait (fig. 3) provides compelling comparative material to her representation as Ophelia or Beatrice. It is a very straightforward portrayal. She is unadorned with her red hair pulled back behind her shoulders, wearing a modest brown dress, and gazing directly at the viewer. Her particularised features, not only reveal a desire for a truthful record of identity/reality, but, along with the three-quarter pose and circular format, reminds us of the Renaissance tondo portraits, linked to public commemoration and memory. While the portrait does not show her in the act of painting, its formal features place her within a long standing artistic tradition. It ultimately suggests that the person depicted is culturally significant enough to be remembered for their achievements.

Figure 3: Elizabeth Siddal. Self Portrait. 1853-3. Oil on Canvas. 9 in. Private Collection.

Art historian Deborah Cherry highlights that Siddal’s self-portrait specifically engages with a format familiar in Northern Renaissance art. Further, she wears a medievalising dress, probably based on a real garment made by her, attesting to her quattrocento interests. Cherry emphasises the notion of encoded “woman as sign” present in the male-dominated Pre-Raphaelite compositions - here challenged by Siddal’s direct gaze as both subject and artist.

When Rossetti painted her portrait in 1854 (fig. 4), after her design, he made a significantly different decision. Siddal’s features are stylised, as though half-fictionalised, while she poses in profile view, with her eyes cast down. The portrait is inescapably one of an enigmatic muse.

Figure 4: Dante Gabriel Rossetti. Portrait of Elizabeth Siddal Facing Left. 1854. Watercolour on wove paper. 28.3 x 24cm. Ashmolean Museum, Oxford University.

On the other hand, Bradley draws out accounts of Rossetti’s regard and encouragement for Siddal’s artistic talents; especially exemplified by a drawing from their holidays at Hastings with their immediate circle. Rossetti’s 1853 drawing Dante Gabriel Rossetti Sitting with Elizabeth Siddal depicts her as an active participant.

Anna Mary Howitt, a Pre-Raphaelite painter, poet, and women’s rights activist who was acquainted with the Rossetti family at Hastings, wrote a novel to claim women artists’ space in the public sphere called The Sisters in Art. Acknowledging the male-centric nature of the Brotherhood, Howitt makes a case for the acknowledgement of female artists not “officially’ a part of it. This is the subject of Wettlaufer’s study, who highlights Howitt's sympathetic portrait drawing (fig. 5) and written reflections on Siddal, highly praising her “genius.” Ultimately, in the long-overlooked private sphere, Siddal was an active participant in the artistic circle as both model and artist; especially supported by other women creatives.

Figure 5: Anna Mary Howitt, Head of Lizzie Siddal, 1854. Pencil on paper. 12.7 × 11.5 cm. Mark Samuels Lasner Collection, on loan to the University of Delaware Library

Furthermore, many scholars have highlighted Siddal’s work as innovative and formative to the redirections of Pre-Raphaelitism. Particularly, her choice to draw inspiration from gothic and medieval illumination and focus on intimate moments. Both Taylor and Shefer highlight Siddal produces a nuanced reading of Tennyson’s Lady of Shalott poem. The Brotherhood tended to depict the drama of the Lady’s grief and impending death as the consequence of gazing at the world directly, rather than through a mirror. Siddal depicts the Lady “ascetic-like” and occupied with her work at the loom while looking outside the window (fig. 6). Shefer specifically reads this as an encoded self portrait of the woman artist reflecting on her position and limited access to the public art world among the Pre-Raphaelites.

Figure 6: Elizabeth Siddal. The Lady of Shalott, 1853, Pen, black ink, sepia and pencil. 6 ½ x 8 ¾ in. Maas Gallery.

Looking back at her Self-Portrait of 1853, her direct gaze, painted by looking at herself through a mirror, evokes her active artistic aspirations, beyond simply being a muse. Just as her Lady of Shalott calmly gazes at the world through the window in spite of her restrictions, she paints herself with a direct gaze vastly different than that of the dying Ophelia or Beatrice.

Bibliography:

Bradley, Laurel. “Elizabeth Siddal: Drawn into the Pre-Raphaelite Circle.” Art Institute of

Chicago Museum Studies 18, no. 2 (1992): 137–87. https://doi.org/10.2307/4101558.

Cherry, Deborah. “Elizabeth Eleanor Siddall (1829–1862).” Chapter. In The Cambridge

Companion to the Pre-Raphaelites, edited by Elizabeth Prettejohn, 183–95. Cambridge

Companions to Literature. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012.

Jan Marsh, Imagining Elizabeth Siddal, History Workshop Journal, Volume 25, Issue 1, SPRING

1988, Pages 64–82, https://doi.org/10.1093/hwj/25.1.64

Rossetti, W. M., Dante Rossetti, and Harold Hartley. “Dante Rossetti and Elizabeth Siddal.” The

Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs 1, no. 3 (1903): 273–95.

http://www.jstor.org/stable/855671.

Shefer, Elaine. “Elizabeth Siddal’s ‘Lady of Shalott.’” Woman’s Art Journal 9, no. 1 (1988):

21–29. https://doi.org/10.2307/1358359.

Taylor, Helen Nina. “‘Too Individual an Artist to Be a Mere Echo’: Female Pre-Raphaelite

Artists as Independent Professionals.” The British Art Journal 12, no. 3 (2011): 52–59.

http://www.jstor.org/stable/41615243.

Wettlaufer, Alexandra K. “Sisterhood in/as the Studio: Anna Mary Howitt’s Sisters in Art” In

Portraits of the Artist as a Young Woman: Painting and the Novel in France and Britain, 1800-1860. Columbus: The Ohio State University Press, 2011. https://muse.jhu.edu/book/24286.