An Art Historian's Guide to Chichester Cathedral

By Elle Borissow

Its recent roof repairs having finally reached completion, now adorned instead with festive candlelight, the enchanting Chichester Cathedral in all its assorted glory awaits your visit. Functionally serving as a place of worship since its building began in 1075 is just the beginning of the rich cultural history held within this structure; its architectural eclecticism organically documenting a wide array of the area’s heritage, today serving as a diverse gallery space alongside its vibrant roster of services.

Just a stone’s throw away from the neighbouring village of Fishbourne and its Roman Palace, Chichester Cathedral – perhaps rather surprisingly – incorporates a section of second-century Roman mosaic through a glass floor panel [Fig. 1]. These small chalk, limestone and brick mosaic tiles belonged to a sizeable room in a former Roman building which lay beneath the foundations of the Cathedral, discovered during maintenance in 1966. By adding a glass portal to “remind […] us of the Roman city of Noviomagus,” which lies about a meter below the surface of modern-day Chichester, such an accepting display of the site’s valuable socio-historical life, despite the differing cultural ideologies of the Romans, makes the Cathedral particularly special in my view.

[Figure 1] Unknown craftsman, Fragments of Roman Floor Mosaic, c. 100-199 AD, stone tile, Chichester Cathedral, Chichester.

In redirecting our gaze from the distant past of ancient Roman civilisation to our contemporary present, more recent commissions such as the Chagall Window [Fig. 2] mark the Cathedral’s “bold […] move into the world of modern art.” Unveiled in 1978, to express a “triumphal quality” on the theme of Psalm 150: “O Praise God in his holiness – Let everything that hath breath praise the Lord,” the Chagall Window, less than a hundred metres away from the ancient mosaic, expresses modern Christian values amidst an expansive display of local history. Captured in fluid marks, the predominance of red in the composition of Charles Marq’s stained-glass is intended to capture this festive mood of praise. The musical imagery of harps, trumpets and joyful merriment echoes the songs of worship heard from the nearby choir chambers , participating in a cohesive belcomposto effect in its casting a jubilant crimson light across this northern area of the Cathedral.

[Figure 2] Charles Marq, Chagall Window, 1978, stained glass window, Chichester Cathedral, Chichester.

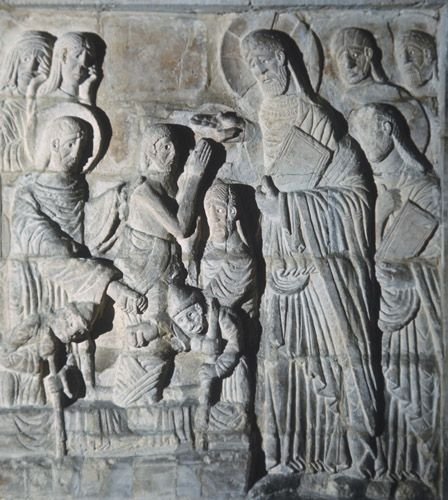

Modern is juxtaposed with historic throughout; one of the oldest artworks in the Cathedral, the twelfth-century Raising of Lazarus relief (c. 1125) [Fig. 3] depicts in stone panels the story described in John 11. 1-44. A wonderful example of this period’s relief sculpture, the Chichester Reliefs are complemented by several Medieval tombs which line the aisles beside the Cathedral’s main body, among which the Arundel Tomb (c. 1375) is a must-see having inspired Phillip Larkin’s 1956 poem, An Arundel Tomb. In terms of an evolving architectural life, the Cathedral’s soaring central chamber maintains the three original stages of the wall – the arcades, triforium, and clearstory with the addition of robust vaulting to a stone ceiling, in replacement of its former wooden version which burnt down in the devastating fires of 1114 and 1187. Further still, the heritage site boasts Britain’s only surviving fully separated medieval bell tower, in addition to the its medieval spire and cloisters from the 1400 renovations.

[Figure 3] The Raising of Lazarus, c. 1125, stone relief, Chichester Cathedral, Chichester.

Adorned with art from across the centuries, including an excellently preserved exemplar of Tudor painting from the 1530s, the Cathedral can be viewed as an example of excellent art stewardship and eclectic curation, thriving as a contemporary site for worship and integrated cultural display. From a musical standpoint, particularly if you fancy something festive, an auditory snippet of the Cathedral Choir’s stunning vocals was featured several days ago on ITV to provide an example of the audial backdrop to this art and architecture.

Though there are so many more examples, my final mention, tucked away amongst the many portrait busts which line the north aisle, is a mixed-media memorial relief sculpture to Ernest R. Wilberforce (c. 1907) [Fig. 4], former Bishop of Chichester, which could be easily overlooked – yet upon inspection its lustrous agate surface rewards the keen artistic eye: the drapery implied on the stone’s polished amber surface shining in the luminous light let in by ample stained glass windows to illustrate a tour de force of the arts.

[Figure 4] Monument to Ernest Roland Wilberforce, c. 1907, mixed media stone relief, Chichester Cathedral, Chichester.

References

A (little) history of the Cathedral | Chichester Cathedral.

“Chichester Cathedral: The Eastern Arm,” in A History of the County of Sussex: Volume 3, ed. L. F. Salzman (London: Victoria Country History, 1935). The British Library Online, accessed December 17, 2023, 116-126.