Dreamers a Century Apart – Francesca Woodman and Julia Margaret Cameron: Portraits to Dream In

By Nicole Entin

What do the nineteenth-century Victorian British photographer Julia Margaret Cameron and the twentieth-century contemporary American photographer Francesca Woodman have in common? One would be inclined to think very little, given their disparate ages, eras, and approaches to the photographic medium. Cameron began her practice at the age of forty-eight and produced around nine hundred images in her lifetime. Woodman, conversely, picked up a camera at the thirteen but her career was cut short with her death at the age of twenty-two. Yet, as the National Portrait Gallery’s new exhibition Francesca Woodman and Julia Margaret Cameron: Portraits to Dream In demonstrates, Woodman and Cameron have far more similarities in their practices than one would expect. I travelled to London through the support of the Trethowan Bursary in the School of Art History to view the exhibition as part of my dissertation research on Julia Margaret Cameron and the resonance of her career with the novels of her great-niece Virginia Woolf. Eager to see how this exhibition shared my goal of bringing Cameron into conversations surrounding modern and contemporary culture, I came away from the NPG truly inspired by what Portraits to Dream In accomplished.

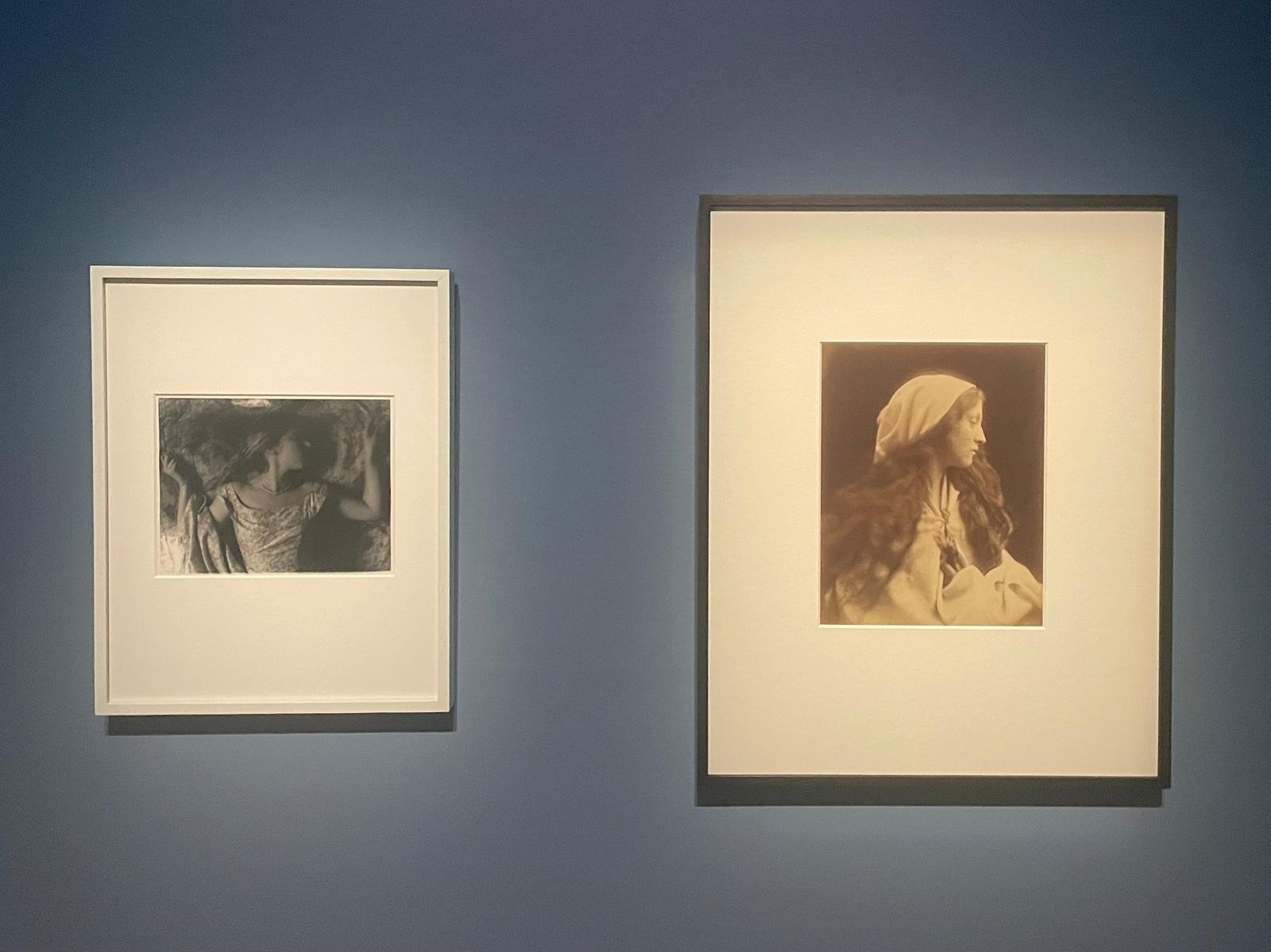

Great exhibition design or academic research projects, I believe, are distinguished by one aspect: the quality of making unexpected ideas or connections seem obvious from the start. Through Magdalene Keaney’s intelligent and visually striking curatorial strategy, Portraits to Dream In entirely succeeded in this goal. At the entrance to the exhibition, viewers could step into a chapel-like alcove with deep blue walls where one self-portrait by Woodman (1979) and an allegorical portrait by Cameron entitled The Dream (1869) [Fig. 1] were positioned alongside each other. The poses of Woodman and Cameron’s sitter – her maid Mary Hillier – are uncannily similar. Their heads are turned in profile, their long and thick hair is worn loose, and their eyes are closed or in a soft downward gaze. Woodman wears an off-the-shoulder evening dress and a string of pearls around her neck, lying on a patterned fabric background with her arms raised – evoking both a sense of falling and falling into slumber in the persistent yet uneasy tranquillity of the image. In Cameron’s image, inspired by the dream vision at the heart of John Milton’s poem ‘On His Deceased Wife’, Hillier wears a white hooded cloak and holds its clasp in her hand. The characteristic soft focus of Cameron’s photography further enhances the dream-like quality of the image, where Hillier’s face is in sharp focus while the edges of the photograph dissolve into light. Two smudged fingerprints are purposefully left on the bottom right corner of the print, reminding the viewer of Cameron’s involvement in the photographic process.

[Figure 1] Left: Francesca Woodman, Untitled, Stanwood, Washington, 1979, gelatin silver print, 187 x 241 mm, courtesy Woodman Family Foundation. Right: Julia Margaret Cameron, The Dream, 1869, albumen print, 305 x 204 mm, the Wilson Centre for Photography. Installation at Francesca Woodman and Julia Margaret Cameron: Portraits to Dream In, 2024, National Portrait Gallery, London.

This pairing that opens the exhibition establishes the clear comparative rationale for the rest of the show, as viewers progress clockwise around the rectangular space. Subtle details emphasise the thought that has been given to the curation of the show. For instance, while Cameron’s photographs are mounted in dark frames, Woodman’s are all in light-coloured frames, visually reinforcing the attribution of each image and emphasising the comparison – especially when the photographs are not paired side by side. The exhibition is organised thematically, grouping images in sections devoted to ‘Picture-Making’, ‘Doubling’, ‘Nature and Femininity’, and ‘Models and Muses’. I particularly enjoyed the section on ‘Angels and Otherworldly Beings’ [Fig. 2], which compared Cameron’s theatrical images of winged women and children with Woodman’s highly experimental Angels series. This was one of the strongest instances in which the unexpected comparison made obvious was evident in the exhibition – one would not be blamed for thinking that Woodman might have actually seen and built upon Cameron’s images.

[Figure 2] Installation view of ‘Angels and Otherworldly Beings’, Francesca Woodman and Julia Margaret Cameron: Portraits to Dream In, 2024, National Portrait Gallery, London.

Another particularly compelling pairing of photographs is found in the ‘Mythology’ section, where a Cameron portrait of Mary Pinnock as Daphne (1866-68) – in which flowers and spiky leaves ominously climb up her chest– is placed alongside a 1980 series of photographs by Woodman where she is pictured with her arms wrapped in birch bark [Fig 3]. Although Woodman’s series is left untitled, the juxtaposition of the photographs with Cameron’s image and their shared themes of femininity and natural transformations immediately underscores their common reading through the myth of Daphne and Apollo, where the persecuted nymph preserves her virtue by transforming into a laurel tree – the leaves of which crowned the greatest poets and artists of the ancient western world. The exhibition thus constructs a subversive women’s artistic heritage that cleverly connects disparate figures throughout the history of photography. The section on ‘Men’ is placed cleverly at the end of the exhibition, emphasising the gallery’s desire to spotlight women artists while placing men in the roles of collaborators, models, and lovers that women typically take in mainstream narratives of art history.

[Figure 3] Left: Julia Margaret Cameron, Daphne (Mary Pinnock), 1866-68, albumen print, 352 x 272 mm, Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford. Right: Francesca Woodman, untitled, MacDowell Colony, Peterborough, New Hampshire, 1980, gelatin silver print, 100 x 102 mm, courtesy Woodman Family Foundation,

The overarching approach throughout the sections juxtaposes Cameron and Woodman’s lives and works in a shared space that Keaney refers to as ‘the Dream Space’: a site that ‘does not constitute the whole of either artist’s practice, but is a central overlapping concern’ encompassing themes common to their practices. (Keaney, ‘Portraits to Dream In’, 13) The rationale of the Dream Space manifests in the evocatively oneiric design of the exhibition, where gauzy translucent screens divide the different sections, and the walls are painted in pale shades of blue and lilac. A room at the midpoint of the exhibition, however, provides a striking change of pace from the rest of the tranquil space. Against a crimson background, Woodman’s colossal Caryatids series (1980) [Fig. 5] is displayed. Three massive prints depict the artist with her arms raised and in various states of partial undress, toned blue through the diazotype printing method. The folds of the skirts or fabric worn by Woodman evoke the fluting of columns, combining soft and hard visual textures. The edges of the prints are rough, and each image conveys a sense of simultaneous stillness and alienation, compelling the viewer to draw to a halt or take a seat on the tactically placed bench in the room. Photography exhibitions are usually confined to displaying items that are small in scale, so the inclusion of the Caryatids created an exciting subversion of expectations and necessary variation.

[Figure 4] Francesca Woodman, Caryatids, 1980, diazotypes, 201.9 x 92.1 cm, 181 x 92.1 cm, 227.3 x 92. 1 cm, courtesy Woodman Family Foundation. Installation at Francesca Woodman and Julia Margaret Cameron: Portraits to Dream In, 2024, National Portrait Gallery, London.

Having studied the work of Cameron for several years while at university, I am thrilled to consider the potential of Portraits to Dream In to introduce Cameron and Woodman’s photography to a wider public, after being considerably overlooked in mainstream narratives of art history. It is both accessible to individuals encountering Cameron and Woodman for the first time, and provides exciting new insights for the knowledgeable visitor. The exhibition creates a cohesive narrative that traces the two artists’ lives side by side and discovers salient points of intersection that both emphasise Cameron’s radical techniques and ground Woodman’s photography in a wider female artistic tradition.