Dear Scotland, Love Craigie Aitchison

By Ilaria Bevan

“There is a moral fierceness in Craigie Aitchison's art that no doubt owes something to his Scottishness…” claimed John McEwan in a short essay about the artist. Amongst all the themes within the painter’s career, there is no better group of pictures that encapsulates this better than his religious scenes - more specifically the Nativity.

Born in Edinburgh on January 13, 1926, Aitchison did not always wish to be an artist. Wishing to follow in the footsteps of his father, Craigie Mason Aitchison who was a judge and lawyer, Aitchison decided to study Law at Edinburgh University which he attended from 1944 to 1946, and continued at the Middle Temple, London in 1948. However in 1950, Aitchison returned to his birth-city to take what was intended to be a temporary break from law studies to informally practise painting.

Photograph of Craigie Aitchison taken in April 1989.

During this time Aitchison decided to convert an old mews house behind his family home on India Street, Edinburgh into a studio where he would paint his first landscape and still life pictures that were subsequently sold at the flower shop next door.

Two years later Aitchison would officially become an artist after enrolling at the Slade School of Fine Art, London from 1952 to 1954. Several of his Slade School contemporaries would turn out to be some of the great British painters working in the second half of the twentieth century including Michael Andrews, Euan Uglow and Victor Willing.

Unlike the School of London artists which comprised of significant figures such as Francis Bacon, Frank Auerbach, Lucian Freud, David Hockney, Howard Hodgkin and Leon Kossoff whose work was dominated by works of a figurative and abstract style, Aitchison and his contemporaries could not be so easily grouped together. Judging their body of work, it would seem that there was no clear connection between this group other than they knew one another from their artistic studies. Furthermore, as John McEwan states, when Aitchison enrolled at the Slade School of fine art he was in his mid-twenties, and therefore able to embark on a more individualistic ruote than his contemporaries.

Critics, scholars and colleagues have also tried to compare him to Mark Rothko and Milton Avery, which (understandably) annoyed Aitchison very much. In many interviews Aitchison states that when he was first likened to Avery by a teacher at the Slade School he was confused, having not encountered any of the artist’s poetic paintings before.

For a contemporary audience, it might seem unusual and old-fashioned for an artist like Aitchison to want to paint religious scenes, particularly given the artistic climate he was working in. More interestingly, Aitchison would not have described himself as a particularly religious person. However, as Aitchison repeatedly stated in interviews, the more questions one asks about his works, the more complicated they become and the same is true for his religious affiliations for, despite his rather liberal religious position, he was interested in Roman Catholicism.

Craigie Aitchison, Nativity and Angels, 1960. Oil on canvas, 40.7cm x 30.4cm.

Nativity and Angels (1960) perfectly demonstrates this sentiment. In a much darker, more sinister palette to his usual bring scarlets and blues, this painting portrays three haloed angels surrounding the Christ child sleeping in the manger. Just outside of the barn where the main action takes place is a thin tree, two animals and a twinkling star.

The meticulous application of paint is easily the most striking feature of the painting. Aitchison, in his delicate handling of oil paint has applied the medium so thinly and so carefully that it bears a striking resemblance to watercolour. Furthermore, the exquisite blending of the brighter shades of red with the darker greys, mauves and blues helps to evoke the mystical atmosphere of this important religious moment.

This effect is achieved by the artist’s decision to paint from the inside out - that is to say that he paints until the final line is achieved. As a consequence, he created no preparatory drawings, nor did he draw on the canvas to map out his composition, instead allowing the colours and shapes to organically materialise. Further evidenced in the lack of detail in the faces and gestures of the figures, as well as the animals by the tree, it seems as if a translucent mist has covered the scene and we, the spectator, are eyeing the scene through this blurred lens. Such a unique manner of painting is perfectly encapsulated in Aitchison’s view of painting as a jigsaw puzzle - if all the colours and shapes fit, then it is complete, no matter the level of detail or naturalism.

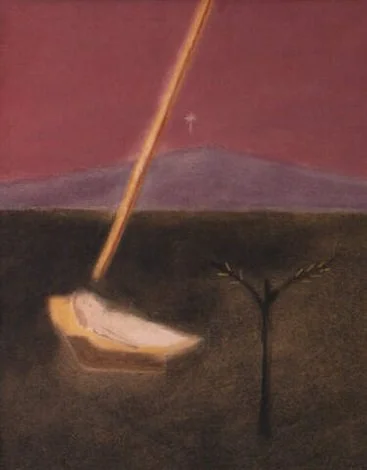

Craigie Aitchison, Nativity, date unsure. Oil on canvas, 31cm x 25.5cm.

One can see this even more clearly in Nativity. Again featuring this tree motif (that is common in a great number of his paintings) the picture portrays the Christ child in a manger, with a brilliant beam connecting the infant to the sky. Drawing our eyes towards the star, which is so lightly brushed on the canvas with white paint so faint it is hard to spot, the yellow and scarlet simultaneously beam provides a sense of dynamism and fantastical mysticism that would have certainly been present in this moment.

Aitchison’s exquisite use of colour could not be better expressed in this picture. Large fields of nearly translucent colour complete the background and invite us to contemplate the beauty of the landscape that can certainly be compared to the unique environments he would have been familiar with in Scotland. Stripped of detail and shading, the fields demonstrate the rigorous selectiveness of Aitchison’s colours and shapes and increases the drama of the composition. Interestingly, he would always paint these background elements of the composition last. However, this is a testament to his independent mind, which McEwan claims is a concept dear to the Scottish.

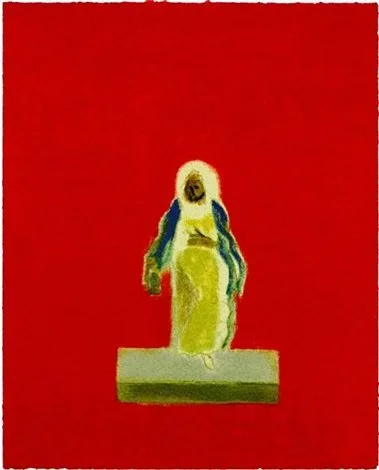

Craigie Aitchison, One of the Wise Men, 2003. Silkscreen printed in colours, 25.7cm x 20.5cm.

However, One of the Wise Men (2003) is strikingly different to these two canvases from earlier in the artist’s career. Painted six years before his death, Aitchison has isolated one of the three wise men - Caspar, Melchior and Balthazar - who delivered gifts of gold, frankincense and myrrh to the Christ child in a bright scarlet backdrop standing on a plinth structure.

This silkscreen print returns to the artist’s earliest palette characterised by brilliant and extremely vibrant colours, which is evidenced in the backdrop and also the royal blue and yellow of the wise man’s costume. Once again the figure’s facial features are blurred, however one can still identify a sense of power and grandeur in the figure’s presence.

Although Aitchison, in an interview with Andrew Lambirth, said that these Nativity scenes were “not so dramatic and exciting” as his canvases portraying the Crucifixion, which would continue to be a central theme within his oeuvre for most of his career, speaking from a spectator’s point of view I would have to disagree. These three pictures mentioned above just provide a small taste of the intense and varied flavour these scenes possess.

Sophisticates would likely view these religious paintings as kitsch or unintelligent, but it is this seemingly simplistic quality that makes that symbolically timeless and completely ambiguous - this is a game Aitchison plays better than anyone else. For me, that's the beauty of Aitchison’s paintings - particularly his paintings on the Nativity subject that reinvigorate this well-known event with a new found sense of tension and drama that was so rarely captured by paintings of this subject.

Bibliography:

Albemarle Gallery. Craigie Aitchison. London: Albemarle Gallery, 1989.

Darwent, Charles. “Craigie Aitchison: Painter renowned for his use of colour who refused to be tied down to a school or genre.” The Independent. Published December 23, 2009. https://www.independent.co.uk/news/obituaries/craigie-aitchison-painter-renowned-for-his-use-of-colour-who-refused-to-be-tied-down-to-a-school-or-genre-1848140.html.

Galeria Ramis Barquet. Craigie Aitchison. New York: Galeria Ramis Barquet, 2000.

Lambirth, Andrew. “Craigie and Sheelagh: Getting it Right.” In Craigie Aitchison: A Private Collection. Edited by Amelia Redgrift, 5-20. London: Waddington Custot Galleries, 2013.

Lambirth, Andrew. “Craigie Aitchison in conversation with Andrew Lambirth.” In Craigie Aitchison. Edited by Timothy Taylor Gallery and Waddington Galleries, 31-38. London: Timothy Taylor Gallery and Waddington Galleries, 1998.

Lambirth, Andrew. “Interview.” In Craigie Aitchison ‘Pictures’. Edited by Peter B. Willberg, 39-48. London: Timothy Taylor Gallery and Waddington Galleries, 2005.

Lambirth, Andrew. “The Intensely Poetic Paintings of Craigie Aitchison.” ArtUK. Published November 17, 2020. https://artuk.org/discover/stories/the-intensely-poetic-paintings-of-craigie-aitchison.

McEwan, John. “Craigie Aitchison.” In Craigie Aitchison. Edited by Timothy Taylor Gallery and Waddington Galleries, 1-10. London: Timothy Taylor Gallery and Waddington Galleries, 1998.

McEwan, John. “Essay.” In Craigie Aitchison. Edited by Sue Grayson assisted by Peggy Armstrong, 7-9. London: The Arts Council of Great Britain, 1981.

McNay, Michael. “Craigie Aitchison Obituary.” The Guardian. Published December 22, 2009. https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2009/dec/22/craigie-aitchison-obituary.

National Gallery of Scotland. “Craigie Aitchison.” Accessed December 15, 2021. https://www.nationalgalleries.org/art-and-artists/artists/craigie-aitchison