Emil Nolde vs Max Liebermann

By Magdelena Polak

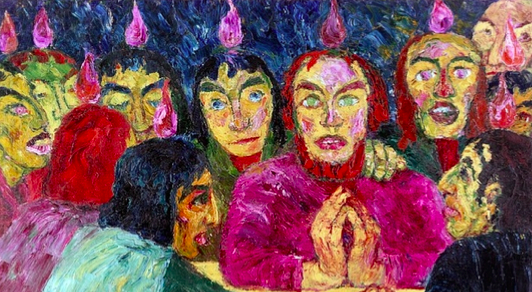

It all began with one painting. Pentecost, painted in 1909 by the Expressionist artist Emil Nolde, now hanging in the Nationalgalerie Berlin. One painting that would mark one of the most controversial fights between artists in the German art world of the 20th century is now one of the primary examples to illustrate the fundamental differences between Expressionism and Impressionism.

Emil Nolde, Pfingsten (Pentecost), 1909

http://www.hausderkunst.de/uploads/pics/Nolde_Pfingsten_146102_detail_630.jpg

In 1909, Emil Nolde was still a struggling artist who had come to Berlin not too long before to establish himself as one of the artists of the Berliner Secession, whose President was the Impressionist painter Max Liebermann. Founded in 1898, the Berliner Secession who decided what was “good” and “bad” art as the trendsetter for all fashions. Liebermann and Nolde differed in more than just artistic style; Max Liebermann was with 63 years the unchallengeable leading figure in the German art world. President of the Berliner Secession, he was regularly honoured with artistic prizes, was known to be charismatic, liked and fashionable. Fighting for recognition for his brand of Prussian Impressionism in his youth, by 1910, he had successfully established it as the artistic movement that everyone who was someone needed to collect, as well as owning one the biggest Impressionistic collections himself, containing no less than 15 paintings by Manet alone, as well as works by Renoir, Monet and Degas.

Emil Nolde, on the other hand, was with 43 years still unknown and, by definition, unsuccessful in the Prussian capital. He was known to be impulsive, uncompromising and incapable of accepting criticism of his work. While Max Liebermann had been very settled in his social position as an artist during the Prussian Regime, Nolde would find it difficult throughout his entire life to be accepted, first in the Prussian Empire, but also in the interwar period and the Nazi Regime. Having been born in a small village in the north of Germany, Nolde’s initial contact with art had derived primarily from visits to the local church on Sundays. There he had come to admire the stone carved altarpiece, which had led him to become an artist. This was a different background to Max Liebermann, who had been born into a rich industrialist family, and had enjoyed private drawing lessons by established artists from a very early age. Clearly, the root of the conflict was personal as much as it was artistic.

When Nolde presented Pentecost to the Berliner Secession in 1910, it was blatantly refused by the institution. Liebermann had previously been quoted to have said of all Expressionism to be nothing more that “smeared blots on canvas”. Having received a letter written by Liebermann’s assistant, Nolde reacted with a public letter in the Berlin newspaper “Art and The Artist”, defaming Liebermann and criticising his work to be old fashioned, weak and kitschy. Because Nolde’s previous experience in the art market had been so humiliating, with no one really understanding his work and the controversy of his character that was both megalomaniac and filled with self-doubt, Nolde felt his refusal at the Berliner Secession to be the last straw, and all this humiliation and self-doubt consolidated in an immense envy for the successful and wealthy Max Liebermann, which eventually became to be hatred for the person itself and the idea he represented- the artistic establishment.

Max Liebermann is reported to have been deeply wounded by the hyperbolic criticism of his artistic skill. Yet he remained professional. While all other members voted for a complete expulsion of Nolde and his work from the Berliner Secession (which would have meant complete bankruptcy), Liebermann was the only one to vote against the expulsion, and as his word carried the most weight, Nolde remained a member. This seems to have angered Nolde even more. He continued his public attacks on Liebermann and, a little ahead of time, found the conspiracy theory that explained it all in his eyes. Both Liebermann and Paul Cassirer, his close friend and the most influential art dealer at that time, were Jewish. Nolde was of the opinion that the two were conspiring with other art critics and denying the younger, more “German” generation the right to step up and take their place as the newly established artistic elite. The fact that most of his other Expressionist colleagues, such as members of the Brücke movement Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, turned away from him at this attitude, did not seem to discourage him.

Once having turned in that direction, Nolde remained a fierce anti-Semitist and would welcome Hitler’s coming into power. Letters remain of him writing to Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels stating his wish to become “First Painter to the Third Reich”.

Interestingly, it is the coming into power of the Nazis that would put Liebermann and Nolde in exactly the same position. Liebermann’s religious faith meant, of course, that his time as a socially influential figure was over, and, as he was too old to leave Germany (he was 85 years old in 1933), essentially forced him to retire completely from public life. Nolde himself was rejected from the Nazi Regime because his artistic style did not meet Hitler’s taste. In fact, the artist would shockingly find out that his works would form the main artworks of the exhibition on Degenerate Art in Munich 1937. His letters to Goebbels pleading to be recognised and stating that he had joined the NSDAP in 1934 did not lessen the blow. He was officially forbidden to paint in 1941. Nolde continued to paint in secret, his most common works of the time between 1941 and 45 being a series of flowers from his garden. While still totally different in style, his work from that period is, interestingly, not too different in subject matter from the flower paintings Liebermann did in the late 1920s until his death in 1935. Perhaps both felt that flowers were a safe subject should they ever be found. Perhaps both felt the creeping horrors that the Nazi Regime would bring, despite their different attitudes towards it, and reacted by focussing on nature’s beauty. Comparisons are definitely able to be drawn between the artists at that time, as the Liebermann Villa proved in 2012, hosting an exhibition called “Max Liebermann and Emil Nolde- Garden Paintings”. I wonder how the artists, especially Nolde, would have reacted had they known that they would ever be exhibited together in such a light.

Emil Nolde, Großer Mohn, 1942

http://www.fnp.de/nachrichten/kultur/Emil-Nolde-Farbenpracht-und-Blumenrausch;art679,773472

Max Liebermann, Blumen bei des Gärtners Haus, 1928

http://de.wahooart.com/@@/8XXCQG-Max-Liebermann-Blumen-bei-dem-Gardener's-Haus

Today, looking at Auction results, it seems clear that Emil Nolde has become a superstar of Expressionism in the late 20th century, whereas Max Liebermann is less known. Nolde’s career, though he was struggling to establish himself for most of his life before 1945, finally kicked off after the war. It could be argued that his being denied to work by the Nazi Regime was a big help in his establishing himself as an artist after 1945, as he could claim to have been yet another victim of the Third Reich. This argument is reinforced by the fact that his autobiography was revised by him personally after the war, leaving out important aspects of his life such as his close contact to Joseph Goebbels, or the fact that he became an enthusiastic member of the NSDAP in 1934.

Yet we must never forget that an artist should be judged (as good as one can) by his artistic skill alone, not his personal character or political attitude. Nolde proved to be an incredibly gifted, powerful, avant-garde Expressionist, otherwise he would not have become an accepted and beloved artist in the latter half of the 20th century, victim or no victim in the period of 1933-45.