The Venice Architecture Biennale: The Good, The Bad, and The Coming

By Blog Editor Martyna Majewska

Once a critical intervention into a long-standing structure has been made, how does one re-establish the old order? Is it possible at all? This seems to be the question facing the curator and the organizers of the upcoming Venice Architecture Biennale.

Porcelanosa-Interiorismo.com

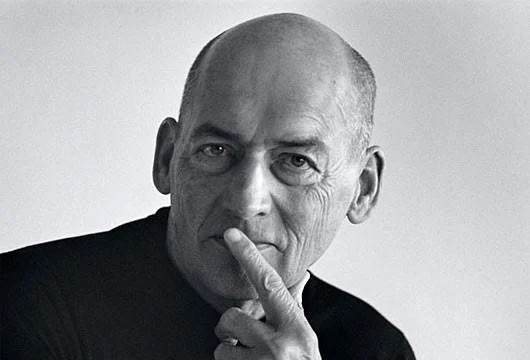

As the celebrated Biennale of Contemporary Art, La Serenissima – as serene as she is – comes to a close, discussions and speculations about the 15th architectural biennial are already underway. This year, the curator, Alejandro Aravena, has to take a step away from not just the distinctive approach employed in the 14th edition but also from the legacy of ideas left behind by none other than Rem Koolhaas.

I don’t think anyone will take offense if I call Koolhaas’s intervention revolutionary. This is not to say his unprecedented approach to the Venice Architecture Biennale came as a shock. After all, he has the renown and the nerve to do whatever he pleases wherever he goes. Koolhaas was the first curator to propose a common theme for all national pavilions: ‘Absorbing Modernity: 1914–2014.’ It was a bold, if not, ironic move on his part since it put an end to the Biennale’s status as a fair for the world’s architectural powerhouses. Instead, Koolhaas encouraged fellow architects to delve into the archive and do some serious research, and he set an example himself by curating the exhibition for the Central Pavilion entitled ‘Elements of Architecture.’

The title was as simple as the idea behind the show: to explore each element of an architectural project: doors, walls, roofs, etc. If you appreciate simplicity as much as I do, you probably think – what a brilliant plan! To start from the very building blocks of architecture, to trace their evolution, and to establish their importance, past and present, seems clever and unpretentious indeed. Yet as much as I liked some of the spaces – notably the breath taking “ceiling” room – others were disappointing to say the least. Of course, the balcony has played a crucial political role since its conception, but to put paper figurines of Mussolini and Hitler on a miniature balcony suddenly seems a bit too simple, if not banal.

Still more disappointing was the execution and spatial organization of the installations, even if the exhibits themselves were stunning. The windows from the Brooking Collection, for instance, were a real treat, but the fact that the visitors had very little space to actually contemplate them somehow deprived the display of its wow factor. Moreover, many objects seemed to have been disposed haphazardly making navigation through the space rather uneasy. Koolhaas’s pavilion proved that archival research is only worthwhile if its results are presented with skill, respect, and attention to detail.

Brooking Collection, Labiennale.org

The same could be argued about the national pavilions, whose curators also grappled with their countries’ past. Koolhaas’s vision for the Biennale exuded a kind of nostalgia about national styles that had been eradicated by modernity. This did not prevent some curators from doing something beyond merely looking back.

I was impressed by the French pavilion, curated by Jean-Louis Cohen. It was refreshing to see a national pavilion unashamedly showcasing the disillusionment and disappointment brought about by modernist architecture, rather than celebrating its innovations. The screening of Jacques Tati’s Mon Oncle provided a playful background to the models and architectural components installed in each room, calling the utopian housing projects into question. Nonetheless, just as the crude execution of the installations in the main pavilion distracted me from inspecting the “Elements” on view, the stuffy atmosphere in the French space and the strong smell of chemicals (possibly paint) made it impossible to focus on the exhibition.

Another positive experience was the visit to the Russian Pavilion, which addressed the importance of the international trade fairs that shaped modern consciousness. The architects created a sort of biennale within a biennale – or a mock biennale to be exact – where each of the numerous booths represented a seminal architectural idea from the 1914-2014 period. This was one of the few successful attempts (the Canadian exhibition being another one) at connecting the ideas and ideals of modernity with the present times. The sheer concept behind the installation made the pavilion stand out from the crowd. Furthermore, unlike the many silent, empty, modernist spaces of other national pavilions, the Russian one was rendered interactive through the presence of assistants who eagerly explained the meaning of each booth.

Finally, the Italian installation at the Arsenale called ‘Monditalia,’ with its stunning Luminaire gate created in collaboration with Swarovsky, proved to be a beautiful spectacle. A Gesamtkunstwerk par excellence, it created an immersive multimedia experience that could please not just to the hoards of architects visiting Venice, but any tourist who happened to stop by. Its success lied in the organization: as a collection of case studies, rather than an overview, it convincingly reflected the multifarious, heterogeneous nature of Italian culture and architecture.

“The Chilean architect seems to be acutely aware that we can no longer regretfully linger on architecture’s loss of diversity and, instead, we need to find practical solutions to the challenges the globalized world faces.”

While Koolhaas’s take on the Biennale encouraged us to ponder architecture’s past, I found it genuinely radical and perhaps rejuvenating. It showed that the Biennale could be a laboratory for architectural research. However, this historical approach cannot be continued and Alejandro Aravena is now forced to redesign the entire format of the festival. The Chilean architect seems to be acutely aware that we can no longer regretfully linger on architecture’s loss of diversity and, instead, we need to find practical solutions to the challenges faced by the globalized world. This does not mean that Aravena is looking for a singular response to the problems nations now have to contend with, notably overpopulation and the ensuing dearth of housing. He strives to enhance the living conditions of humanity at large, while not disregarding the particularities of each situation. After Koolhaas’s insightful but rather static show, the only solution appears to be a decisive move forward. Aravena’s theme, ‘Reporting from the Front,’ announces a battle but, unlike a military conflict, this one is supposed to bring about hope and concrete projects for the future. Although we have yet to discover what his exact propositions are, the theme he has proposed looks very promising. For one thing, being Rem Koolhaas’s successor may prove quite liberating – nobody expects you to beat probably the most famous living architect, but if you do – and it does not seem that hard – you might end up taking his place.